From Noah to Abraham to Moses: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, Part 2

Biblical genealogies have often been used to attempt to calculate a date for creation which is then cited as support for a young Earth. However, closer examination of the ancient Hebrew reveals evidence for gaps in these genealogies, making them unsuitable for such calculations. The story of Moses, in particular, demonstrates just such a gap.

In part 1 of this series, we discuss the fundamental importance of the Hebrew word yālad—commonly translated “begat” (KJV) or “became the father of” (NIV, NASB)—in calculating biblical dates such as creation and Noah’s flood. Date-setters assume yālad implies a parent-child relationship in the biblical genealogical passages. However, the story of Moses seems to demonstrate that yālad implies only a general familial relationship, and hence offers strong evidence of genealogical gaps in the biblical record.

Consider Amran and Jochebed, the couple commonly referred to as Moses’ “parents.” The Bible records Amram as the grandson of Jacob’s third son, Levi (Exodus 6:16, 18). Amram married Jochebed, Levi’s daughter and Amram’s aunt, who yālad (“bore”) Moses to him (Exodus 6:20; Numbers 26:59). Moses is described as the bēn (“son” or “child”) of Amram in the genealogical records in 1 Chronicles 6:3 and 23:13.

English translations of the Bible thus make it appear that Moses is the son of Amram and Jochebed. However, closer scrutiny of the text suggests this is impossible. Based on chronological information in the Bible, we calculate that Amram would have been at least 216 years old (362 max.) at the time of Moses’ birth. Yet according to Exodus 6:20, Amram died at age 137! There must be a gap in Moses’ genealogical records. (Our calculations are detailed and charted in the appendix at the end of this article.)

Similarly, Jochebed would have been at least 255 years old (350 max.) at the time of Moses’ birth. If this were true, then the story of Sarah bearing Isaac at age 90 (Genesis 17:17, 21:5) would pale in comparison—yet the Bible puts great emphasis on it as a miracle of God. In light of Isaac’s story, it seems unlikely Scripture would fail to even comment that Moses was born to a woman of such advanced age—especially since he is the third child in a seemingly routine family in which his siblings, Aaron and Miriam, were both only a few years older than he.

It should be noted that genealogical gaps can occur before or after a named individual. That is, the gap might be between Levi and Amram/Jochebed or between Amram/Jochebed and Moses. However, the detail provided in the narrative appears sufficient to conclude that it is the latter in this case. As Old Testament scholar William Henry Green observed, “Amram and Jochebed were not the immediate parents, but the ancestors of Aaron and Moses.”1 Hence, yālad as used in Exodus 6:20, Numbers 26:59, and 1 Chronicles 6:3, 23:13 means Moses is a descendant, not a son, of Amram and Jochebed—proving a gap in Moses’ genealogical records.

As an additional demonstration of this hypothesis, the initial census of the Israelites after the Exodus from Egypt provides strong evidence there must have been many generations between Moses and Amram and Amram’s father, Kohath. The census records 8,600 male descendants of Kohath who were at least a month old, including 2,750 between the ages of 30 and 50 (Numbers 3:27–28, 4:35–37). At 80 years old, Moses himself was among the older descendants of Kohath at the time of the Exodus. Yet if Moses was Kohath’s grandson, it seems unlikely Kohath would have this many 8,600 male descendants in the Exodus, including 2,750 only one generation younger than Moses.

The Importance of Hārâ in Parent-Child Relationships

Furthermore, note that Exodus 2:1–2a (NASB) does not name Moses’ parents:

Now a man from the house of Levi went and married a daughter [bat, “daughter” or “female relative”] of Levi. The woman conceived [hārâ] and bore [yālad] a son.

Note also the difference between the verbiage used in these verses and the genealogical record. Moses’ unnamed mother both conceived (hārâ) and bore (yālad) him, whereas only yālad is used when referring to Jochebed’s relationship to Moses. This difference seems to reinforce the suggestion that although Amram and Jochebed are Moses’ ancestors, they are not his parents.

A logical question is, if Amram and Jochebed are not Moses’ parents, why are they named in his genealogy, while his actual parents are anonymous? The answer may be found in Leviticus 18:12 (NIV): “Do not have sexual relations with your father’s sister.” The relationship between Amram and Jochebed was contrary to the laws God gave through Moses (even though these laws were not given until later). Amram and Jochebed may be considered importantbecause they are illustrative of a relationship that God later defined as sinful. God, through Moses, may be making the point that He knows us intimately, including the less attractive details. This may be the same reason the Bible makes other disclosures such as:

- Genesis 38 details the illicit relationship2 between Judah and his daughter-in-law Tamar, while taking scant notice of the marital affairs of Jacob’s other children.

- Exodus 6 mentions that one of Simeon’s sons was “the son of a Canaanite woman” (Exodus 6:15, NASB), but says nothing about Simeon’s other wives. Abraham had insisted that Isaac must not marry a Canaanite (Genesis 24:1–4) and Isaac was “displeased” when Esau took Canaanite wives (Genesis 28:8, NASB).

- The only women mentioned in Jesus’ genealogy (Matthew 1:3, 5–6) are Tamar, Rahab the prostitute, Ruth the Moabitess, and Bathsheba the adulteress.

In fact, the use of hārâ and yālad with Moses’ parents in Exodus 2:1–2 may provide the key to possible gaps (or lack thereof) in biblical genealogies. It seems hārâ (or a derivative of hārâ) or a birth narrative in another form is typically used whenever the biblical author wishes to establish a definite parent-child relationship. We cannot claim this is always the case; yet hārâ or a related form or term often appears—with or without yālad—in stories about other prominent biblical characters:

- Cain and Abel (Genesis 4:1–2)

- Enoch (Genesis 4:17)

- Ishmael (Genesis 16:4–5)

- Moab and Benammi (Genesis 19:36)

- Isaac (Genesis 21:2)

- Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah (Genesis 29:32–35)

- Dan and Naphtali (Genesis 30:5, 7)

- Issachar and Zebulun (Genesis 30:17, 19)

- Joseph (Genesis 30:23)

- Er and Onan (Genesis 38:3–4)

- Perez and Zerah (Genesis 38:18)

- Samuel (1 Samuel 1:20)

- Obed, David’s grandfather (Ruth 4:13)

It might be said that hārâ represents the physical, whereas yālad represents the consequential. If only the word yālad appears, one is cautioned to be alert for possible genealogical gaps. A parent-child relationship is guaranteed only if hārâ or a related form or term is used (or if there is a birth narrative); otherwise the precise relationship is unknown. Readers of English Bibles should be wary of “begat” (KJV) or “became the father of” (NIV, NASB) unless a parent-child relationship is established otherwise.

We are not claiming that gaps occur in all genealogical records in which only yālad appears; we are only claiming that we cannot be sure one way or the other. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that hārâ or a related form or term never appears in Genesis 5, 10, or 11, nor do these chapters include unambiguous birth narratives. Hence, genealogical gaps are a real possibility in these passages especially—and these passages are particularly crucial for the calculations of biblical date-setters.

Yet whatever the reason for the gaps in Moses’ personal genealogy, this example makes it clear that genealogical gaps are a Mosaic phenomenon. If Moses inserts a gap into his own genealogical record without mention, it is probable that the concept of an unbroken genealogy is not important to him and that gaps are likely found elsewhere in Mosaic literature, perhaps especially when the author is dealing with things more distant from his own historical moment.

The next part of this series investigates the story of Noah’s sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. It will show how the assumption that yālad always and literally means “begat” (KJV) or “became the father of” (NIV, NASB) in Genesis 5, 10, and 11 presents a hermeneutical problem ignored by biblical date-setters.

Appendix: Calculations for Amram, Jochebed, and Moses

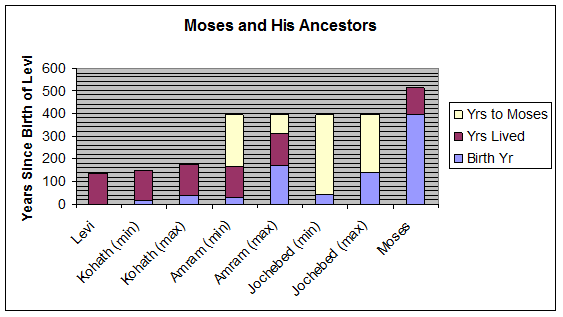

The chart and details below demonstrate how we calculated chronological information for Moses’ family, specifically for Amram and Jochebed.

All dates are with reference to Levi’s birth date, four years (±1 year) before Joseph. The top of the blue bars indicate date of birth. The purple bars indicate the person’s lifetime. In cases where birth and/or death dates must be estimated, two bar graphs are provided: one for the earliest birth date and one for the latest. (Since Jochebed’s lifespan of is unknown, only her maximum and minimum birth dates are included.) The yellow bars indicate the time between the person’s earliest and latest dates of death and the birth of Moses. (In the case of Jochebed, this is between the earliest and latest birth dates.)

The arrival of Jacob’s family in Egypt (under Joseph’s sponsorship) provides a good reference point for calculating the relative chronology for Amram, Jochebed, and Moses. The years before descent into Egypt are designated as “BD,” and the years post descent into Egypt as “PD.”1 When it is not possible to precisely calculate a person’s age, a range is calculated, assuming a man fathers a child no earlier than age 15 (puberty at age 14), and no later than on his deathbed (even though in the case of Kohath fathering Amram, this seems ridiculous).

Joseph’s chronology is well documented, providing a good basis for estimating Amram’s and Jochebed’s chronology. Joseph was the last son born to Jacob in Paddan Aram, apparently at the very end of Jacob’s second seven years of service to his father-in-law (Genesis 29:20–30, 30:25–26). He was sold into slavery at age 17 (Genesis 37:2) and entered the service of Pharaoh at age 30 (Genesis 41:46–47, 45:11). This would have made him 37 when the famine began (Genesis 41:47), and 39 at his family’s descent into Egypt with five years of famine remaining (Genesis 45:11). Hence, Joseph was born 39 BD.

Levi was Joseph’s older brother and Jacob’s third son. The Bible records that Jacob sired 12 children with four mothers in seven years (six of these offspring with Levi’s mother, Leah). Since there are no multiple births, this is biologically possible only if Leah’s pregnancies occur as quickly as possible, and this is what we assume. Hence Levi was probably born three years after Jacob’s marriage to Leah and Rachel, and Joseph was born four years after Levi. Since Levi lived 137 years (Exodus 6:16), we assume Levi was born 43 BD and died 96 PD.

Kohath is the second of Levi’s three sons (Genesis 46:8–11) and lived 133 years (Exodus 6:18). He descended into Egypt with the family (Genesis 46:8–11). Therefore, we assume his birth could have occurred as early as 27 BD (a year after his older brother, when Levi was 16), and as late as 2 BD (a year before his younger brother, who also descended into Egypt). This puts Kohath’s earliest death at 107 PD and his latest at 132 PD.

Amram was the first of Kohath’s four sons and he lived 137 years (Exodus 6:18–20). Based on Kohath’s own earliest birth plus 15 years, we assume Amram’s earliest possible birth is 12 BD—but it could be as late as 1 PD if Genesis 46 includes a complete list of Jacob’s offspring who descended into Egypt. Making the improbable assumption that all four of Kohath’s sons were conceived in the last four years of his own life, we put Amram’s latest possible birth date at 130 PD. Therefore, his earliest possible death was 126 PD and the latest was 267 PD.

Jochebed is the wife of Amram and daughter of Levi (Exodus 6:20). Her earliest date of birth is 1 PD—since she was born in Egypt (Numbers 26:59)—and her latest was 96 PD (assuming deathbed conception by Levi). Her age at death is unknown.

Moses was 80 years old at the time of the Exodus (Exodus 7:7), 430 years after the descent into Egypt.2 Hence Moses was born around 351 PD.

Simple math now shows us that in the year of Moses’ birth, 351 PD: Amram’s age would have been between 216 (minimum) and 362 years (maximum)—up to 225 years beyond his recorded lifespan. Jochebed’s age would have been between 255 (minimum) and 350 (maximum) years.

Even with the wide ranges noted above, errors are possible since we had to estimate the birth and death dates for Levi, Kohath, Amram, and Jochebed. However, these estimates should not be more than ±10 years off, thus, still sustaining the basic conclusion.

Dr. Hugh Henry received his PhD in Physics from the University of Virginia in 1971, retired after 26 years at Varian Medical Systems, and currently serves as a lecturer in physics at Northern Kentucky University in Highland Heights, KY.

Mr. Daniel J. Dyke received his Master of Theology from Princeton Theological Seminary 1981 and currently serves as professor of Old Testament at Cincinnati Christian University in Cincinnati, OH.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Endnotes

- William Henry Green, “Primeval Chronology,” Bibliotheca Sacra (April 1890): 293.

- “Do not have sexual relations with your daughter-in-law” (Leviticus 18:15, NIV).

Appendix Endnotes

- Note that one year must be added to the calculations going from BD to PD—just as in going from BC to AD—because there is no year 0.

- Bishop Ussher’s chronology changes this to 215 years. In this instance, Ussher follows the Septuagint (LXX), which adds an extra phrase to Exodus 12:40: “and the land of Canaan.” Adding this phrase, which is not found in the Hebrew text, implies the 430 years are counted between the time Abraham departed Haran (Genesis 12:4) and the Exodus: 215 years between Abraham’s departure and Jacob’s descent, and 215 years between Jacob’s descent and the Exodus. In his book A Survey of Israel’s History (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), Leon Wood argues persuasively that the Hebrew text is correct.

Since Ussher’s chronology usually follows the Hebrew text, his choice to follow the LXX in this case may imply that Ussher and the LXX translators were aware of the Amram/Jochebed/Moses problem, because the LXX resets Moses’ birth year to 136 PD, and makes it possible for Amram and Jochebed to be his parents because their age ranges at his birth would be 1–147 and 40–135 years, respectively. Nevertheless, although a parent-child relationship is possible, it still seems unlikely because for Jochebed to be only 40 at Moses’ birth, she would have been the product of a deathbed conception by Levi; and if Jochebed is 90 when Moses was born (Sarah’s age at Isaac’s birth [Genesis 17:17, 21:5]), Jochebed would have been conceived when Levi was 91 years old.

Hence Moses’ birth using LXX dates would still almost certainly be a miracle like Isaac’s, and our argument stands: it seems unlikely Moses would fail to mention this.