Pursuing the Truth

I received an inquiry recently from someone wanting to know what it meant to follow the truth scientifically and theologically. In other words, when there are competing explanations in theology and science respectively, how do you follow the truth in each discipline?

To properly answer that question, let me first outline a model for how science and theology relate to one another in a Christian worldview. Historic Christianity affirms that God reveals himself in a specific way (through the words of the Bible) and in a general way (through his work in creation). To quote my colleague Ken Samples, “God is the author of both the figurative book of nature (God’s world) and the literal book of Scripture (God’s written Word).”

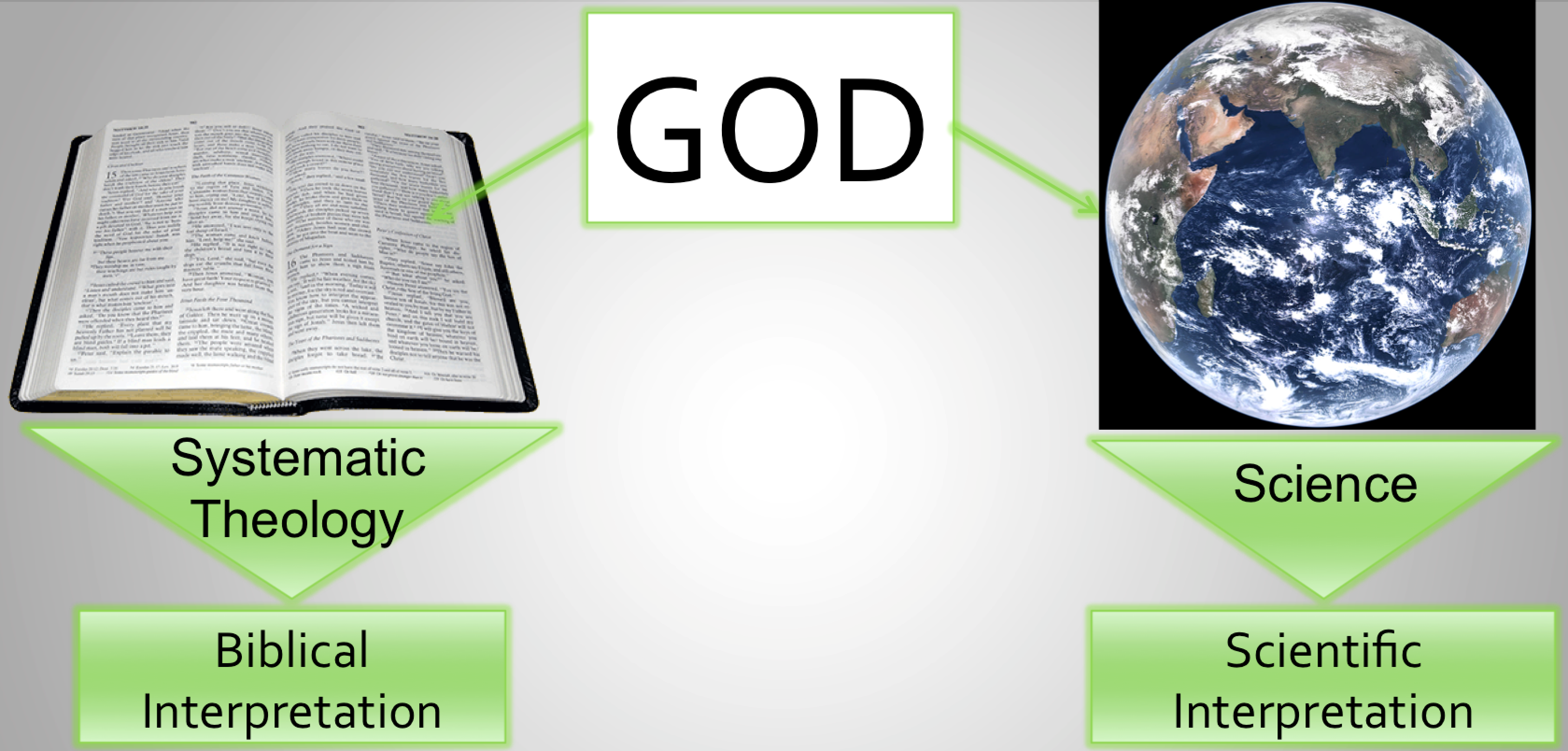

Because God is the source of both revelations, they must both be true and they both must agree. If we had God’s mind, perhaps this simple statement would be the end of the discussion . . . but we don’t. We cannot simply see revelation (either special or general) and understand it. Instead, we must carefully study and analyze revelation to come to a proper interpretation. For purposes of making a diagram, I use the term systematic theology to describe the process of interpreting the biblical texts. Similarly, science is the term to describe our study and analysis of creation.

While both revelations must agree (because they are derived from God’s nature), our interpretations of those revelations can conflict. Where we see conflict, that is a signpost of an inaccurate interpretation of either the record of nature or the words of the Bible.

So, how do you pursue truth when theology and science seem to conflict? Basically, you test each interpretation to ensure the highest possible accuracy in both. Scientists do this all the time. Different experiments give conflicting results, so they design more detailed experiments to resolve the conflict. For example, one of the key projects of the Hubble Space Telescope was to resolve conflicting measurements (or interpretations, if you will) of the Hubble constant. And scientists in different disciplines often encounter phenomena that requires both disciplines to understand. It took the application of physics and geology to understand the natural nuclear reactors at Oklo and Bangombé.

Often, people claim that theology and science are in conflict. Many of these conflicts arise from trying to make the data say more than it does. On one hand, some Christians claim that the Bible demands a universe/earth that is a few thousand years old—but not all legitimate interpretations of Scripture make this demand. On the other hand, some atheists claim that science explains everything without the need for a God. Even if this were true, science does not justify the philosophical presuppositions necessary for science to operate (but a Judeo-Christian worldview does).

Also, we must also recognize that neither gives us a complete picture of reality. Although the Bible clearly provides all we need to know for a right relationship with God, it was never meant to give exhaustive truth. The universe “speaks” a less precise language and science is largely limited to physical explanations. However, in my studies so far, I have yet to encounter a genuine contradiction between the words of the Bible and the facts of nature. I have encountered numerous conflicts in our interpretations, but as I dug deeper one of two scenarios occurred. Either there was not enough data to truly answer the question at hand or the two revelations ultimately agreed. That is exactly the outcome I would expect if God created the universe and then inspired the biblical authors to pen the words they did!