Why Is It So Hard to Eat Healthy?

Knowing what constitutes a healthy diet is necessary for making wise food choices, but with all the conflicting nutrition information online and in the media, it is sometimes difficult to find the truth. Yet, even the consumer with the least knowledge of nutrition knows that an apple is a better choice than a candy bar. So although some poor food choices can be chalked up to inconsistent and poor nutrition information, the better food choice is often obvious. And there are foods we can consume with confidence, knowing that the Bible and all the diet doctors agree they are good for us (see previous blog post “Do Nutrition Scientists and the Bible Agree on What Constitutes a Healthy Diet?”).

The Human Condition

Even when we know what foods are good for us, it is difficult to eat as we should. We eat sweet, salty, and highly refined foods that are low in nutrients despite knowing such foods are not good for our bodies. We know a small shake has fewer calories than a large, but we still choose the large even when we want to eat fewer calories. This is the human condition: we know what we should do, but don’t have the self control to do it.

The Bible accurately describes this universal human condition through the words of the apostle Paul: “For what I am doing, I do not understand; for I am not practicing what I would like to do, but I am doing the very thing I hate” (Romans 7:15, NASB). In our fallen state we often give in to desires of the flesh that aren’t the best for our health. The main problem, then, of consuming a healthy diet seems to be our inability to do it, not the lack of knowledge about proper eating. But even in our fallen state, there are practical steps we can take to make the healthy choice the easier choice.

Step 1: Decrease Portion Sizes

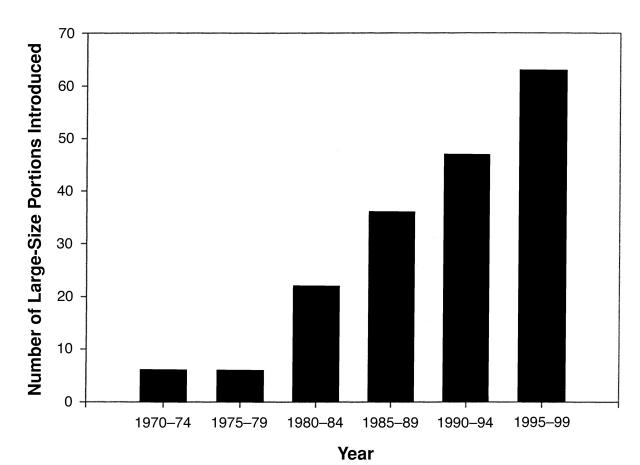

The first step is to reduce portions—not by restricting certain foods, but by changing the dining environment to be more like it was in the past. Historically, portion sizes—as well as eating utensils (e.g., plates, bowls, and silverware)—were much, much smaller. The following graphic shows the number of larger sizes introduced during the last quarter of the twentieth century.1

Figure 1: . Credit: Lisa R. Young and Marion Nestle, 2002

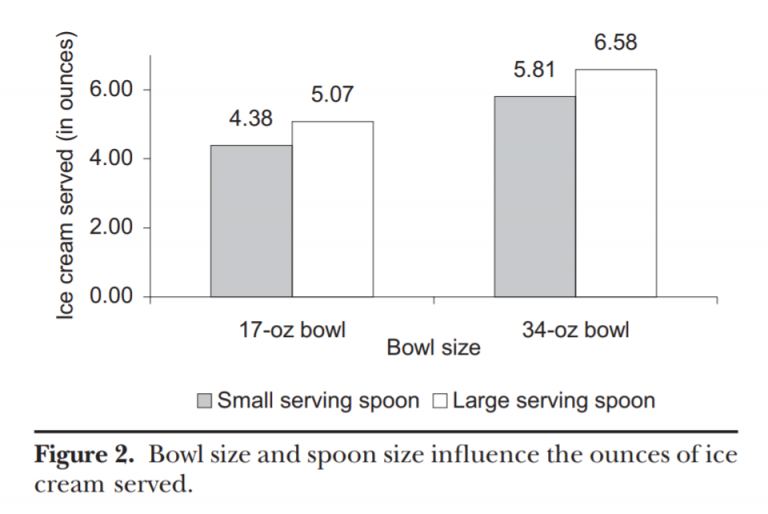

One obvious way to reduce calorie intake is to choose smaller portions, but this is easier said than done. The following study demonstrates that simply by decreasing the size of eating utensils, portions are naturally reduced.

Figure 2: Ice Cream Consumption Varies by Bowl and Serving Spoon Size. Credit: Wansink, van Ittersum, and Painter, 2006

This study was conducted a second time on CBS’ The Early Show and it yielded the same results: simply changing the size of eating utensils can help us eat less at every meal.

Step 2: Limit Visibility and Accessibility of Food

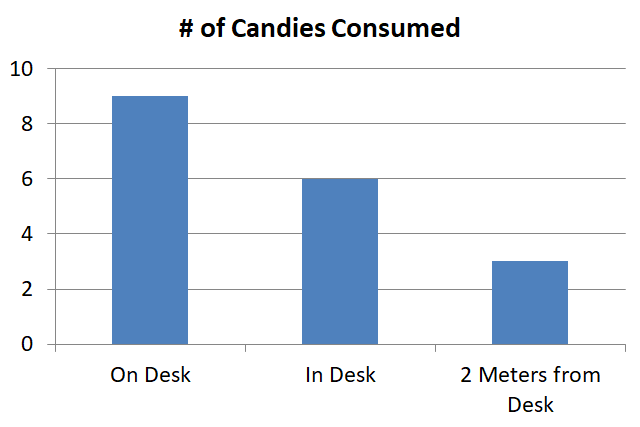

The second step is to make food less visible and accessible. We are on a “seefood diet”—meaning if we see it, we’ll eat it. Simply keeping food out of sight and slightly less accessible will decrease consumption. Researchers conducted a study with office employees working at their desks for eight hours. Candy kisses were placed in three different locations on alternate days: on the desk, in the desk drawer, and in the cabinet two meters away. Moving the candy from the desktop (visible and convenient) to the desk drawer (invisible but convenient) decreased consumption by 30%, and candy moved to the cabinet (invisible and inconvenient) decreased consumption by 60%.3

Figure 3: Candy Consumption by Visibility and Proximity. Credit: Painter, Wansink, and Hieggelke, 2002

Considering the human condition, adopting these first two steps allows us to consume less without having to make conscious decisions to do so at the point of consumption. They help prepare the way long before eating takes place.

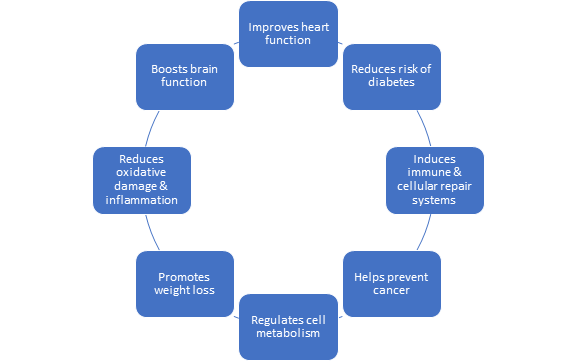

Step 3: Fasting

For most of human existence, food wasn’t readily available in unlimited portions. For centuries, fasting was an integral component in many religious traditions, including Judaism. Jesus himself never told his disciples to fast. He assumed they would when he said, “Whenever you fast” (Matthew 6:16, NASB). Recent research on fasting has discovered many health benefits for reducing the risks of dementia, heart disease, and diabetes.4 It isn’t necessary to go on an extended fast to get the benefits. Simply reducing the number of hours we eat in a day to 6–10 consecutive hours can produce results.

Figure 4: The Positive Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Credit: Adapted from Ferah Armutcu, 2019

The Biblical Solution

The natural solutions given above don’t actually solve the human temptation to eat more than is necessary, but provide only palliative ways to help. Paul gives the answer: “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” (Romans 7:25, NASB) The answer lies in the person of the Lord Jesus Christ. When we accept his atoning sacrifice for our shortcomings, he comes to live within us through the Holy Spirit and gives us the power to do what is right, including how to take care of our God-created bodies. Scripture not only describes the human condition in great detail, but it also gives impetus to correct wrong ideas: “We are destroying speculations and every lofty thing raised up against the knowledge of God, and we are taking every thought captive to the obedience of Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5, NASB). It’s tempting to spend the day dreaming about and lusting after junk food. We need to cast down those thoughts and set our minds on the things above (Colossians 3:2). Wrong choices follow wrong thoughts. Considering that Paul still struggled with not being able to do what he knew he should, it is expected that we would have the same struggles.

Although nutrition knowledge is important in making good food choices, the bigger part of the issue is more likely our inability to choose the foods we know we should eat. The Bible explains this dilemma and provides the answer—the God of the universe has come to live with us and in us to give us the ability to do the things we know we should do. Bon appétit!

Endnotes

- Lisa R. Young and Marion Nestle, “The Contribution of Expanding Portion Sizes to the US Obesity Epidemic,” American Journal of Public Health 92, no. 2 (February 2002): 246–49, doi:10.2105/ajph.92.2.246.

- Brian Wansink, Koert van Ittersum, and James E. Painter, “Ice Cream Illusions: Bowls, Spoons, and Self-Served Portion Sizes,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 31, no. 3 (September 2006): 240–43, doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.003.

- James E. Painter, Brian Wansink, and Julie B. Hieggelke, “How Visibility and Convenience Influence Candy Consumption,” Appetite 38, no. 3 (June 2002): 237–38, doi:10.1006/appe.2002.0485.

- Ferah Armutcu, “Fasting May Be an Alternative Treatment Method Recommended by Physicians,” Electronic Journal of General Medicine 16, no. 3 (May 2019): doi:10.29333/ejgm/104620.