Blaise’s Best Bet, Part 2: Pioneering Physicist

Despite dying in 1662 at age 39, French philosopher Blaise Pascal left a mark on mathematics and science still present to this day. Part 2 of this series on Pascal’s intellectual legacy focuses not only on his practical contributions to math and science, but also on his influence on the philosophy of science. (See part 1 for an introduction to Pascal.)

Mathematician, physicist, inventor

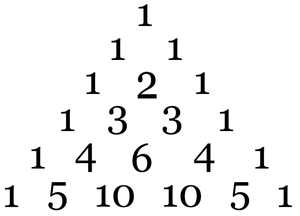

Throughout his adult life, Pascal made important contributions to the field of mathematics. His fertile mind succeeded in laying the foundations for infinitesimal calculus, integral calculus, and the calculus of probabilities.1 In fact, a major developer of calculus, German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), credited Pascal’s infinitesimal analysis with inspiring his own breakthroughs in calculus.2 Pascal also contributed to the disciplines of geometry and number theory.

Philosopher Richard H. Popkin says of Pascal, “[His] analysis of the nature of mathematical systems seems to be closer to 20th-century mathematical logic than that of any of his contemporaries.”3

Pascal was also considered a first-rate experimental scientist. He diligently practiced the then-emerging scientific method by rigorously testing, and verifying or falsifying his observations and conclusions. His most important scientific achievement may have come in his work as a physicist. Many credit his original experiments with air pressure and the nature of vacuums as laying the foundation for hydrodynamics and hydrostatics.4

Like all truly great inventors, Pascal’s technological intuition and productive imagination made him a man far ahead of his times. His creative technological experimentation resulted in the invention of the syringe, the vacuum cleaner, the hydraulic press, and in the development of the first public transportation system in Europe. His most famous invention, however, resulted from his attempt to help his father avoid the arduous task of calculating taxes.

Pascal became convinced that if a clock could calculate the hour, then a machine could also successfully perform mathematical calculations. He then proceeded to invent a mechanical adding device that was, essentially, the first digital calculator. Today Pascal’s calculator is considered one of the first applied achievements of the early scientific revolution and the precursor to the modern computer5 (hence, the reasons acomputer-programming language was named after him).

Philosopher of science

Pascal possessed an astute understanding of and appreciation for the new science born and nurtured in seventeenth-century Europe.6 An avid supporter of Copernicus and Galileo’s views (still considered radical at that time), Pascal argued that respect for authority should not take precedence over analytic reasoning and scientific experimentation.

He explored the nature of the scientific method and of scientific progress, specifically addressing the importance of experimental data and the need to develop sound explanatory hypotheses. He asserted that as scientists continued to explore nature’s mysteries, newer and more updated hypotheses would and should replace presently accepted ones.

Pascal also recognized the limits of science. He believed that while scientific theories can be confirmed or falsified, they can never be absolutely established. This, as Popkin points out, is a position quite similar to the one advocated by Karl Popper, an eminent twentieth-century philosopher of science.7 Pascal was also aware that scientific progress had not changed human nature; he knew that the process by which human beings form their basic beliefs is never purely rational or empirical.

Contemporary Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft has said of Pascal, “He knew the power of science, but also its impotence to make us wise or happy or good.”8 Because of his forward thinking, some have called Pascal “the first modern man.”

But his innovative thinking extended beyond the empirical realm. In the forthcoming editions of this series, we’ll look at Pascal’s conversion to Christianity and his profound impact on apologetics and theology.

Endnotes

- Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, vol. 4 (New York: Image Books-Doubleday, 1994), 154–55.

- Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, s.v. “Blaise Pascal.”

- Ian P. McGreal, ed., Great Thinkers of the Western World(New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1992), s.v. “Blaise Pascal.”

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy, reprint ed. (1972), s.v. “Blaise Pascal.”

- McGreal, Great Thinkers of the Western World, s.v. “Blaise Pascal.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Peter Kreeft, Christianity for Modern Pagans: Pascal’sPensées Edited, Outlined and Explained (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993), 9.