Why Is Atheism So Appealing?

Our Culture of Selfishness

A T-shirt I saw recently in a train station stated: “The love of my life is myself.” For many people, selfishness has not only become fashionable but also the acknowledged basis for existence. Instead of feeling shame for being selfish, one’s social value is often measured by the uniqueness of one’s image or by the number of “likes” on social media. Academics and politicians tell people that they can be whoever they want to be, and advertisers appeal to selfish instincts by insisting that everyone deserves whatever they want.

Our culture seems to be playing a desperately competitive game of “look at me!” (or look at my image). Even people who are not naturally charismatic, attractive, or clever can attract attention by dressing or acting in ways that cause others to look at them. But what if that doesn’t work?

In contrast, the Christian message encourages humility, self-denial, and acknowledgment that we are creatures in a universe created by a sovereign, loving God in whose care we find our purpose. But this idea is not appealing today, as it appears that humans would rather be their own gods.

So How Did We Get Here?

Long ago, Epicurus (341–270 BC) argued that unchangeable atoms, from which everything is made, implies that the universe is eternal, so gods are not needed. However, this atheistic line of thought was buried by the Romans and the church until the Renaissance.1 Cultural acceptance of atheism came about gradually as humans became increasingly able to explain natural phenomena without invoking God. This increased understanding culminated in the nineteenth century with Charles Darwin, who needed an infinitely old universe to support his theory of evolution based upon competitive natural selection (survival of the fittest2). Later that century, Friedrich Nietzsche’s declaration that “God is dead”3 influenced many academics, and God’s irrelevance has since been taken for granted by many influential cultural and academic leaders.

This trend has persisted despite a growing disconnect between science and atheism, and growing agreement between science and theism.4 Twentieth-century science (and beyond) has undermined fundamental atheistic assumptions because atoms are changeable and there was a creation event. Organizations such as Reasons to Believe offer many resources that show how scientific research points to God’s active existence.

Even so, Darwin’s and Nietzsche’s ideas prevail. There is nothing new or modern about “survival of the fittest.” It shows up in chapter 3 of Genesis. There, the serpent reveals his competition with God for the hearts and souls of mankind by stirring up mistrust of God, fanning our desire to be godlike and blame God for evil. Darwin identified natural competitive processes and proposed that they can account for everything humans perceive and experience. While humans cannot actually create a universe like God has, we emulate him virtually with video games, in computational simulations of the big bang, and by being kings, queens, or emperors.

No God, No Suffering?

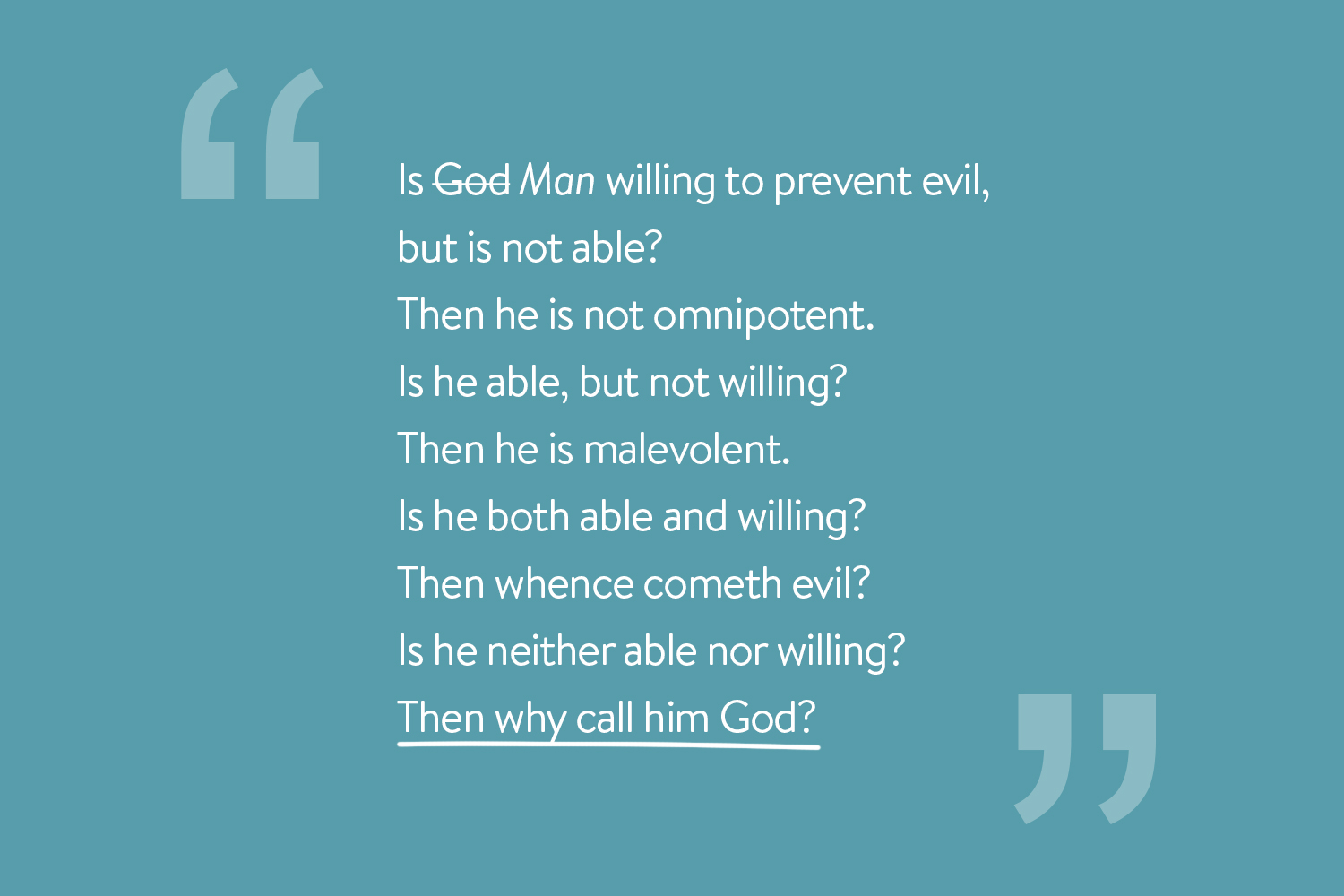

If God is dead in our culture, then only humans can give meaning to life. Ironically, this humanistic view nullifies a potent argument about suffering attributed (incorrectly5) to Epicurus to negate God. Substituting “Man” for God in this statement describes our human experience rather accurately:

Without God, the source of suffering can only be the consequence of human behavior (i.e., someone else has damaged me) or natural causes. While many claim that God is dead, we—like gods—want to judge and set rules that most favor our natural skills and inclinations (this is more natural to us than eating). Saying that God does not exist does not address the problem of evil or suffering, which would need to arise from the decisions made by oneself, others, or natural disasters. Even calling it “evil” or “suffering” seems inconsistent with a Godless creation. The existence of evil and suffering tells us that something is wrong in the world, and that there are standards outside of ourselves that we all recognize.

Is Winning All There Is?

Though we might state that God is dead, irrelevant, or meaningless, there is nothing we would rather be than God. Even if one does believe in God, it is often a god that reflects what we think God should be like—a designer god created in our own image that best suits our own needs. This designer god might be a human role model we admire. Thus, there is no higher authority above ourselves than the men or women who gain the admiration and support of the most people, which enables the “winners” to define what is valuable. Thus, it’s possible for individual men and women to achieve at least a local or temporary godhood. Roman emperors declared themselves to be gods. In our time, rock stars, world leaders, famous athletes, and tech geeks have attained godhood. Their images are on our T-shirts—and many of us would like to be on t-shirts, too.

A culture based upon competition and “survival of the fittest” implies that there are only a small number of “winners.” Do the “losers” then have no value? If their role is to support the winners, they are by definition a lower class. Any of us who aspire to godhood will find it unbearable to submit to those who claim to be more fit, so the “most fit” are in constant danger of being replaced. But it’s lonely at the top, and no one can be trusted. If there’s no one to trust, then life becomes painfully lonely, and loneliness leads to despair. Hence, the lifetime of a local god is limited by their toleration of being lonely.

No.

Against the cultural trend, centuries of scientific knowledge affirms that God may not only exist, but may even be necessary to account for what we know. Science enables the technology we all depend on to live in a high-tech world, but if we declare ourselves to be our own god, we become a walking contradiction. How? Our ability to be our own god depends on the science that recognizes the existence and authority of God. Thus, we become double minded, or culturally schizophrenic.6

Would our troubled minds be healed if we recognized our limitations and asked God to help us become like him in the way that God intended? Is the Creator of the universe and the Author of life trustworthy? Countless people through the millenia have thought so. “Taste and see that the Lord is good” (Psalm 34:8). If he is, this recognition requires our willingness to let God regenerate our hearts and rewire our brains. In Jesus’s words, “For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it” (Matthew 16:25).

Endnotes

- This historical narrative is explored by Benjamin Wiker in Moral Darwinism: How We Became Hedonists (Westmont, IL: IVP Academic, 2002).

- Herbert Spencer coined the phrase “survival of the fittest” after reading Darwin’s Origin of Species, which used “natural selection” for the same idea. See University of Cambridge, “Survival of the Fittest,” Darwin Correspondence Project. Accessed August 25, 2023.

- In The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs (1882), Friedrich Nietzsche recognized that the atheistic perspective killed God, and foresaw the collapse of culture that was built upon Christianity.

- This harmony (as well as the anthropic principle and biological complexity) is explored extensively in the books of Hugh Ross and colleagues at Reasons to Believe.

- This trilemma attributed to Epicurus was published by David Hume in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, part X (1779) and is discussed by Jason Sylvester in the context of his book in progress, Dangerous Ideas. You can read an excerpt in “‘Then Why Call Him God?’—Epicurus Never Said What Everyone Thinks He Did,” Medium, November 26, 2020.

- The letter of James recognizes this problem (James 1:7–8).