Why Isn’t God Present and Unambiguous?

What is the greatest challenge to God’s existence and his goodness?

Some would say it’s the problem of evil. If God exists and he is good, why is there so much seemingly senseless pain and suffering in the world?

Others might say it’s God’s hiddenness. If God exists and he is good, and wants us to acknowledge and worship him, why doesn’t he make himself and his wishes clearly known to us?

This is the challenge I received from someone on X (formerly Twitter) in response to an article I posted presenting scientific evidence for God’s role in life’s history. He wrote:

I’ve followed Hugh and yourself since around 2008 or so and valued your perspectives. . . . In my mind, if any of this was true, we wouldn’t have to have these discussions. This God of the universe would be present and unambiguous.

Divine hiddenness presents one of the most serious challenges to Christian theism. There are good responses to the problem. However, if truth be told, none of the responses “feel” fully complete, nor fully adequate.

Divine Hiddenness and God’s Transcendence

In response to the problem of divine hiddenness, theologian and philosopher Michael Rea writes:

God’s transcendence should be understood as implying that all of God’s intrinsic attributes—divine love included—elude our grasp in ways that should put us in doubt about any revelation-independent claim about how a perfectly loving deity would likely behave toward human beings.1

Rea’s point is that if, indeed, God is transcendent, his hiddenness is endemic to his nature. As creatures who are part of his creation, we have no hope of being aware of or experiencing a transcendent God who exists outside and independent of the universe. We can only know God if he chooses to reveal himself to us.

The Islamic concept of God embodies Rea’s understanding. In Islam, God is entirely hidden from us, and, therefore, unknowable to us. Muslims intertwine God’s greatness with his hiddenness. All we can know of Allah is what Allah wills. (And Allah wills what Allah wills.) To say that we can somehow know Allah is considered blasphemy because to know him means that we are in some way his peers. We are elevating ourselves to his level when we say we can know him.

The Doctrine of Revelation

Considering the Islamic concept of God’s hiddenness, the Christian doctrine of revelation becomes quite radical. According to the doctrine of revelation, the transcendent Creator of the universe, who is intrinsically hidden from us, has chosen to make himself known to us. From Scripture, it appears that this Creator wants us to see his attributes in that which he has made, and desire to be in a loving relationship with him.

According to Christian theologians, God has made himself known from:

- that which he has made (which is the basis for the cosmological and design arguments),

- our conscience (which is the basis for the moral argument), and

- human nature—human beings bear God’s image and, consequently, we image God.

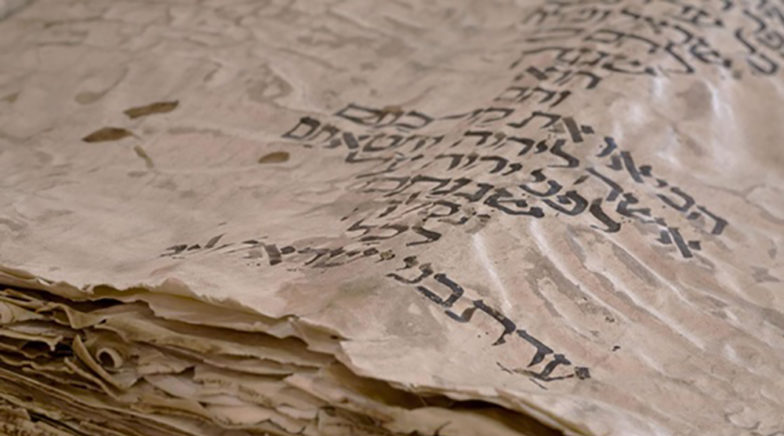

Theologians refer to this form of revelation as general revelation because it’s generally available to all people at all times. Theologians also describe a second type of revelation: special revelation. Here God has revealed himself to specific people, at specific times, under specific circumstances. These interactions with God have been written down and recorded in the pages of the Old and the New Testaments.

God’s ultimate revelation of himself is in the person of Christ—God incarnate.

Some Remain Skeptical

As a Christian, it’s clear to me that God has made himself and his desires for all humanity abundantly known. I find the case for the Christian faith to be compelling. But I recognize that others don’t. Many skeptics remain sincerely unconvinced that God exists. They assert that this “revelation” is still unclear and ambiguous, leaving room for a skeptic to sincerely question God’s existence and goodness.

I’m sympathetic to that point. To be fair, the conclusions drawn from cosmological, design, and moral arguments bear an element of uncertainty. The likelihood that the conclusions ring true can be in the “eye of the beholder.” Likewise, while the evidence for Jesus’s life and crucifixion is certain, the case for Christ’s resurrection is probabilistic.

Based on my reading of Scripture, I’m not surprised by ongoing skepticism in the face of divine revelation. Scripture teaches that some people will not see God revealed through his creation (Romans 1:19–25). In fact, there were people who directly experienced Jesus’s ministry firsthand, yet rejected him as the Messiah. So why wouldn’t that be true today?

Space for Sincere Unbelief

God has chosen to make himself known to us, yet it seems like he’s left space for sincere unbelief.

Why wouldn’t God be clearer in his revelation to us? This question brings us back to Michael Rea’s thought. As creatures, we don’t get to dictate the manner and the extent to which a transcendent God makes himself known to us. Yet his revelation to us must be sufficient because there are many people like me who do see God’s fingerprints in creation, who are convinced that Jesus rose from the dead, and who have encountered God through religious experiences.

Philosopher Michael Murray has suggested two related possibilities for God’s ambiguity in revealing himself to us. First, he argues that if God made his existence undeniable, it would strip us of moral freedom. As a result, we would be coerced into following his moral mandates. We wouldn’t really have the freedom to choose to obey God.2 Second, he argues that God’s hiddenness is essential to “soul-making.” For people to develop and grow and be transformed in their innermost being, they must possess free will. They must be able to choose wrong from right, good from evil.3

Yet, if God is revealed so plainly and his will made unambiguous, then we would be so overwhelmed by God that we would have no choice but to believe in him and follow his commands. Our free will would be stripped from us, and our souls could not be transformed.

Another point related to Murray’s arguments is the idea that God created humans in his image to be in a relationship with him. He made us with a free will so that we could choose him or reject him. Any relationship becomes meaningless if one person in the relationship compels the other person to be in the relationship with them and to love them. If God made himself unambiguously known to us and his desire for a relationship with us were undeniable, we wouldn’t have any choice whatsoever. We would be compelled to believe in him and serve and worship him. If this scenario were the case, then it would render God a megalomaniac, not a God of love, grace, and mercy.

In short, God has good reasons for not making himself ever-present and his desires for us unambiguous. We can ascertain some of the reasons, but others may remain unknown to us. Still, just because we don’t know (or can’t know) those reasons doesn’t mean they don’t exist in the mind of a transcendent God.

Resources

- Without a Doubt: Answering the 20 Toughest Faith Questions by Kenneth Samples (book)

- Christianity Cross-Examined: Is It Rational, Relevant, and Good? by Kenneth Samples (book)

Divine Hiddenness

- “Is God’s “Hiddenness” a Rational Objection to Christianity?” by Kenneth Samples (article)

- “Heaven and the Hiddenness of God” by Sean Oesch (article)

- “Is God Hidden from Us?” by Joseph Palmer (article)

Endnotes

- Michael C. Rea, The Hiddenness of God (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 8–9.

- Michael J. Murray, “Coercion and the Hiddenness of God,” American Philosophical Quarterly 30, no. 1 (January 1993): 27–38.

- Michael J. Murray, “Deus Absconditus,” Divine Hiddenness: New Essays, ed. Daniel Howard-Snyder and Paul K. Moser (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 62–82.