Life’s Twists and Turns Are Designed to Start in the Birth Canal

“Life is full of surprises and serendipity. Being open to unexpected turns in the road is an important part of success. If you try to plan every step, you may miss those wonderful twists and turns. Just find your next adventure—do it well, enjoy it—and then, not now, think about what comes next.”

Condoleezza Rice

Anyone who has lived for a while knows that life is full of twists and turns, unplanned and unexpected happenings that shape our destinies—for good and for bad.

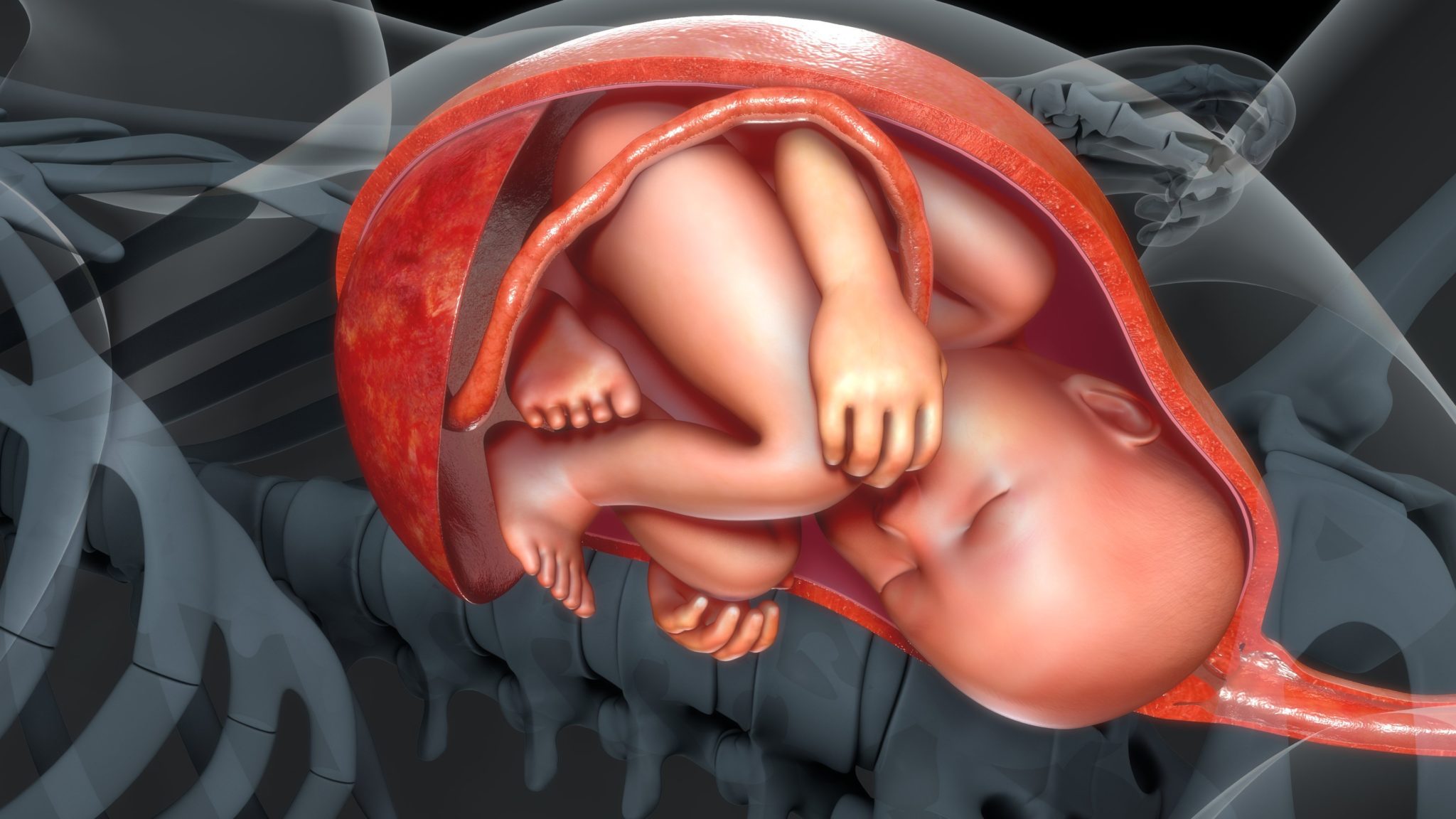

Biologists have come to learn that life’s twists and turns begin even before we’re born. In fact, we all experience our share of twists and turns during the birthing process because of the shape of the human birth canal. The inlet to the birth canal is transversely (left to right) oval (or round, in some cases). The mid and lower part of the birth canal is longitudinally (front to back) oval. When the birthing process begins, the baby enters the birth canal with the longest dimension of its head aligned with the widest dimension of the birth canal. The twisted birth canal forces the baby to rotate and reorient as it makes its way through the birth canal. If the baby’s head becomes misaligned, it can result in obstructed labor, which can be deadly.

A Challenging Question for Creation Proponents

Even though many people try their best to put life’s unexpected twists and turns in a positive light, the twists and turns that babies face during the birthing process appear to have no obvious upside—at least, at first glance. Its peculiar shape prompts the question: Why is the human birth canal twisted?

This question carries biomedical importance and theological significance. In fact, it takes on urgency for people (like me) who advocate for a creation model approach to biology. Why would God create human beings—the crown of creation— with such a dangerous and difficult birthing process?

This question packs an even more powerful punch when the birthing process of humans is compared to that of old-world monkeys (native to Africa and Asia) and the great apes. Both groups of primates have a uniformly shaped birth canal, with the inlet, middle, and outlet possessing a longitudinally oval shape. This uniformity makes for a relatively easy birthing process compared to that of humans.

I must concede that it wouldn’t be unreasonable for a skeptic to conclude that the twisted human birth canal is another example of a flawed biological design best understood as a consequence of an unguided and historically contingent evolutionary history. In this view, evolutionary mechanisms “make use of” preexisting biological systems (for example, the longitudinally oval birth canal of the great apes) to “cobble together” new ones (in this case, the twisted human birth canal). To counter this skeptical perspective, it is incumbent upon proponents of a creation model to identify sound reasons for the twisted human birth canal.

New Insight on the Human Birth Canal

A team of researchers from Austria has discovered that the architecture of the human birth canal is no accident. By using biomechanics principles to analyze the twisted human birth canal, they found that its design appears to reflect a necessary trade-off between several competing requirements that humans uniquely face—given our large brain size, upright posture, and bipedal locomotion.1

Based on biomechanical considerations, the Austrian researchers discovered that the design of the human birth canal reflects a trade-off between (1) minimizing the deformational stress experienced by the muscles in the mother’s pelvic floor and (2) the constraints that arise from upright posture and bipedal locomotion (walking erect).

Their calculations indicate that the design of the birth canal found in old-world monkeys and the great apes appears to be ideal for those species. Both (1) an oval shape and (2) longitudinal elongation of the birth canal minimize the deformational stress experienced by the pelvic floor muscles during the birthing process. (Excessive deformational stress can lead to pelvic floor dysfunction, which can have lifelong consequences.)

The team’s calculations also indicates that the longitudinally oval shape of the mid and lower birth canal in humans is, likewise, ideal for humans.

But If the inlet of the human birth canal was also a longitudinally oval shape, it would cause problems because humans walk upright. A longitudinally oval inlet into the birth canal would force excess curvature of the spine and greater pelvic tilt. While this shape would facilitate the human birthing process, it would also compromise the spinal health of the mother by placing undue shear stress on her vertebral discs. Greater pelvic tilt and spinal curvature would also lead to a loss of stability, making it a challenge for human females to adopt an upright posture. On the other hand, the researchers discovered that a transversely oval shape to the human birth canal inlet reduces the pelvic tilt and spinal cord curvature, protecting the mother’s spine from injury.

Because old-world monkeys and great apes are quadrupeds, they can tolerate a birth canal with a longitudinally oval inlet. Hence, the Austrian researchers argue that their analysis indicates that the complex shape of the human birth canal evolved under the influence of antagonistic selection effects arising from (1) the birthing process, (2) pelvic floor stability, and (3) the demands of an upright posture and bipedalism.

Based on a creation model perspective, I interpret their findings differently. From my vantage point, the research team’s work highlights a previously unrecognized set of intentional design trade-offs.

It is commonplace for engineers to be confronted with trade-offs when they design devices or systems intended to perform a variety of competing functions. To overcome trade-offs, engineers must intentionally introduce suboptimal features into their designs in order to achieve an overall optimal performance for the device or system.

In other words, thanks to this new insight, the twisted human birth canal no longer poses an intractable problem for creation models. Instead, the human birth canal can be rightly understood as an optimal, well-designed system that expertly manages competing design priorities.

Evolutionary Constraints or Constraints of the Archetype?

Yet, based on my experience, sophisticated skeptics who are versed in evolutionary theory will not accept my argument. They will insist that even though the design of the human birth canal may well be optimal, it is still more reasonable to view it as a product of evolutionary history in which the evolutionary pathway to the human birth canal was constrained by its natural history. Accordingly, evolutionary processes “work” with existing systems, “modifying” them in response to the pressures that come from natural selection. In this case, the modified inlet (and, consequently, the twisted birth canal) is understood to be a concomitant evolutionary response to the evolution of our upright posture and bipedalism.

In light of this perspective, I have often heard skeptics ask, Why wouldn’t a Creator with infinite power and infinite resources design humans in such a way as to avoid trade-offs, such as those that lead to a twisted birth canal just so we can walk on two legs? It’s a fair question. For this reason, I have addressed it elsewhere. (See Resources for Further Exploration.)

In effect, skeptics are arguing that God should have created human beings with a unique anatomy and physiology to specifically accommodate our bipedalism. If he did, however, it doesn’t mean that the design of the human body would be free of trade-offs. They are inevitable for complex systems, such as the human body. It’s just that the trade-offs would appear somewhere else.

From a creation model perspective, trade-offs in biological systems arise, in part, from the constraints of the archetypical designs shared by organisms that naturally group together. Prior to the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, biologists such as the eminent Sir Richard Owen interpreted shared biological features as arising from archetypical designs that existed in the Mind of the First Cause, designs manifested in biological systems as homologous structures.

Owen marveled that the archetypical designs that define the anatomy of organisms that naturally grouped together were robust enough that they could be varied to produce biological systems to carrying out a wide range of functions. In a presentation to the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Owen stated,

“The satisfaction felt by the rightly constituted mind must ever be great in recognizing the fitness of parts for their appropriate function; but when this fitness is gained as in the great-toe of the foot of man and the ostrich, by a structure which at the same time betokens harmonious concord with a common type, the prescient operations of the One Cause of all organization becomes strikingly manifested to our limited intelligence.”2

Drawing inspiration from Owen, creation proponents could view the twisted human birth canal as a modification of the archetypical design of the primate birth canal that has been intentionally restructured to accommodate our upright posture and bipedalism. Accordingly, it is remarkable that the design of the mammalian birth canal is so robust that it can be varied to accommodate two distinct modes of locomotion: knuckle-walking quadrupedalism and upright bipedalism.

Designed for Discovery

There is another conceivable reason why God could have created life’s diversity using archetypical designs: discoverability.

The universal nature of biochemistry and biological systems is fortuitous for life scientists. These features allow them to generalize what they learn by studying one organism to the entirety of the biological realm, in some instances. For example, by studying the anatomy and physiology of the birth canal in one group of mammals, scientists can generalize what they learn to all mammals, including humans.

The universal and homologous designs in biology also allow the scientific community to use organisms as model systems. Where would biomedical science be without the ability to learn fundamental aspects about our biology by studying model organisms such as yeast, fruit flies, and mice? How would it be possible to identify new medications if not for the biochemical similarities between humans and other creatures?

Conversely, if the Creator used a near infinite array of biological designs, it would be challenging to study the living realm. The process of discovery in biology would become cumbersome and laborious.

Because the living realm is intelligible, it is possible for human beings to take advantage of God’s provision for us, made available within creation. As we study and develop an understanding of the living realm, we can deploy that knowledge to benefit humanity—in fact, all life on Earth—through agriculture, medicine, conservation efforts, and emerging biotechnologies.

Resources for Further Exploration:

The Elegant Design of Human Reproduction

“The Remarkable Scientific Accuracy of Psalm 139” by Fazale Rana (article)

“Placenta Optimization Shows Creator’s Handiwork” by Fazale Rana (article)

“Recent Insights into Morning Sickness Bring Up New Evidence for Design” by Fazale Rana (article

“If God Hates Abortion Why Do So Many Occur Spontaneously in Humans?” by Fazale Rana (article)

“The Female Brain: Pregnant with Design” by Fazale Rana

“Curvaceous Anatomy of the Female Spine Reveals Ingenious Obstetric Design” by Virgil Robertson (article)

Design Constraints of the Archetype

“Archetype or Ancestor? Sir Richard Owen and the Case for Design” by Fazale Rana

“Q&A: Why Would a Limitless Creator Face Trade-Offs in Biochemical Designs?” by Fazale Rana

“Q&A: Why Would an Infinite Creator Employ the Same Designs?” by Fazale Rana

“Duck-Billed Platypus Venom: Designed for Discovery” by Fazale Rana

Endnotes:

- Ekaterina Stansfield et al., “The Evolution of Pelvic Canal Shape and Rotational Birth in Humans,” BMC Biology 19 (October 11, 2021): 224; doi:10.1186/s12915-021-01150-w.

- Richard Owen, On the Nature of Limbs: A Discourse, ed. Ron Amundson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 38.