Personal Observations on Allan Sandage’s Spiritual Journey

Over the past decade, many people have asked for my perspective on the spiritual journey of renowned astronomer and cosmologist Allan Sandage. Although I certainly would not claim to know every detail of his story, I’m glad to share what I know from conversations with Allan and observations made over more than thirty years of acquaintance. For readers who may not be familiar with Dr. Sandage, let me first introduce the scientific accomplishments for which he is widely recognized.

Sandage, the Astronomer

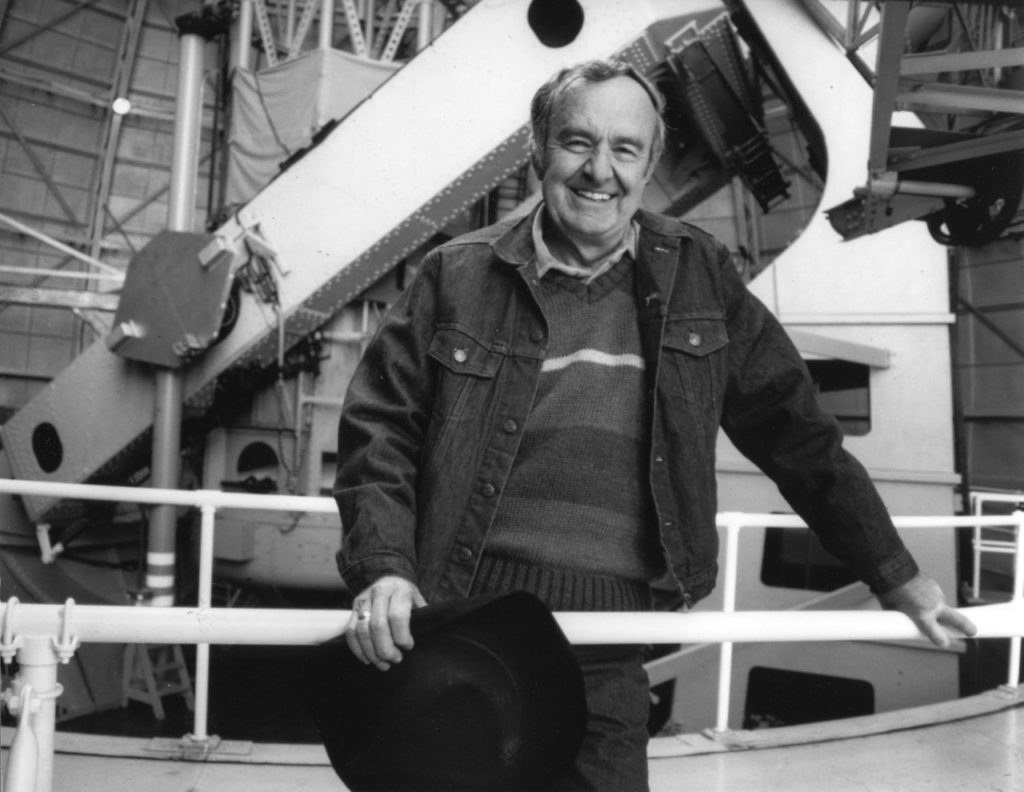

From the 1950s to the time of his death in 2010, Sandage ranked among the world’s most influential and productive astronomers. Some would say that he was the most accomplished astronomer. He received his PhD in 1953 from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) under the supervision of astronomer Walter Baade. While a graduate student, he served as the assistant to leading observational cosmologist Edwin Hubble. Baade and Hubble taught Sandage the observing techniques that enabled the young astronomer to gather the highest quality data then-current technology allowed.

When Hubble died suddenly in 1953, Sandage took over Hubble’s project to measure the cosmic expansion rate and age of the universe. In 1958, he published the first reliable measurement of the cosmic expansion rate, better known as “the Hubble constant.” His published rate (75 kilometers/second/megaparsec) came remarkably close to the rate that current technology affirms. From the 1950s to 1990s, Sandage was regarded by his peers as the preeminent observational cosmologist of his time. He also researched and wrote broadly on the origin and history of our galaxy, of globular clusters, of stars, and of the Sun, and he found time to publish two exquisite galaxy atlases.

With over 500 papers in the peer-reviewed astrophysical literature, in addition to several books, Allan was described by his peers as ambitious. Having had many opportunities to see him at work at the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, I would attribute his prodigious output to a passion for research and a strong work ethic, qualities he exhibited until his death from pancreatic cancer at the age of 84. I must add that he sometimes expressed disdain for astronomers who lacked a strong work ethic or meticulousness in their research.

Sandage’s research earned him multiple awards, medals, and prizes, including the Helen B. Warner Prize for Astronomy, the Eddington Medal, and the National Medal of Science. He is perhaps best known for winning the Crafoord Prize. Worth $2 million, this is astronomy’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Sandage, My Friend

I first met Sandage through his research papers during my late teen years. Having decided from an early age to pursue a career in astronomy, I was inspired by Sandage’s papers to focus on observational cosmology, albeit through the use of radio, not optical, telescopes.

One reason for choosing Caltech for my postdoctoral research was the opportunity it provided for rubbing shoulders with many of the world’s leading astronomers. Not only was Caltech the preeminent astronomy research university at the time, but the campus was just two miles from the headquarters for the Carnegie Observatories, and this proximity would allow me to meet and possibly collaborate with Sandage. Alas, when I arrived at Caltech, I learned of the “great divorce.” After decades of a close working relationship between the Caltech and Carnegie astronomers, disputes had intensified to the breaking point.

Almost to a person, the Caltech astronomers blamed Sandage for the divorce. I learned not just from the Caltech colleagues but also from researchers at other institutions that Sandage had a reputation for feuding with peers. It was said that you were a nobody in astronomy unless Sandage had stopped talking to you.

I first saw Sandage in person shortly after beginning my postdoctoral research. Because my office was next to the astronomy department library, I would see him whenever he needed access to an item from the Caltech collection. I also observed his interactions with astronomers and physicists who gathered in the library for refreshments and conversation before our departmental lectures. He always seemed nervous, high-strung, and testy. Nevertheless, his sarcastic humor often elicited uproarious laughter, even from his so-called “enemies.”

While my fellow astronomers accused Sandage of refusing to interact with any astronomer who disagreed with him, my observations told me otherwise. Sandage showed loyalty and genuine warmth toward fellow astronomers who, whether they agreed with his research conclusions or not, demonstrated a strong work ethic, attention to precision in their observations, and a high regard for integrity. The enduring friendship between Sandage and Halton (Chip) Arp serves as an example. Sandage strongly promoted big bang cosmology while Arp strongly opposed it. However, Sandage openly lauded Arp as a superb observer, saying that any observational result Chip had produced could be trusted. Based on Sandage’s endorsement, I went to Chip whenever I needed a redshift measurement on one of the radio sources I was tracking.

Sandage’s Journey to Faith

I was a full-time researcher at Caltech for three years and part-time for two more. While conducting research, I began attending and then accepted an invitation to join the pastoral team at a church located near Caltech, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the Skeptics Society headquarters, and Fuller Theological Seminary. My primary task at the church was to teach people about the harmony and consistency between God’s two books, the book of Scripture and the book of nature, and to show them how this connection could help break through people’s barriers to faith in the Bible’s redemptive message.

My pastoral responsibilities included mobilizing and equipping church members to visit newcomers to our Sunday worship services who had given us their contact information. Our task was to welcome them, answer any questions they had, and offer any spiritual encouragement and/or practical assistance they needed.

One Tuesday morning in 1980, I was surprised to see “Allan Sandage” on one of these cards. My initial response was to assume that another Allan Sandage must be living in the Pasadena area. No way could this card be from the Allan Sandage. However, when I checked local directories, I found only one such listing. So, I decided to make this visit myself, taking with me a young man named Scott, who was new to the Christian faith.

When Scott and I knocked on the door of his home, Allan greeted us warmly and invited us in. He seemed pleased to see us and said he had two important questions for us. His smiling, relaxed manner made me think I must be seeing a different Allan Sandage, or certainly a transformed one. He seemed quite different from the man I had observed a few years earlier.

Before getting to his two big questions, Allan first had some personal questions. He asked each of us to describe how we had come to faith in Jesus Christ, and he seemed pleased to hear our stories. He was especially intrigued that a church had recruited me, a Caltech astronomer, to serve on its ministry staff. He joked that although he remembered hearing my name, at least I wasn’t on the list of Caltech astronomers he was trying hard to forget.

When I asked Allan what had prompted his visit to our church, he told us a little of his story. During his early years, he had been exposed to Judaism first, and then to Mormonism, but he rejected both and adopted an atheistic worldview. However, despite his atheistic stance, he felt drawn to read and study the Bible. Allan told us that for 35 years he had been studying the Bible, off and on, and had finally become convinced that it’s true. He had decided to become a follower of Jesus Christ, acknowledging that God would have to help him live as a Christian.

Based on his understanding of Hebrews 10:25, he saw the need to find a place where he could grow and develop as a Christ-follower. So, using a phone directory, he assembled a list of sixty-six churches within a relatively short driving distance of his home. With that list in hand, he drove to one or more of those churches each Sunday and parked his car where he could observe the people walking into and out of the building. He said he was looking for three things: people carrying Bibles, people bringing notepads, and people showing, by their expressions and interactions, that what they learned that day mattered. From these observations, Allan narrowed the list of churches from sixty-six to six.

For each of the remaining six prospects, he told us, his plan was to attend their services for six consecutive Sundays and fill out whatever registration card or guest book he found. His goal: to determine whether the church cared enough about his spiritual status and needs. Our church was the last of the six. He said he liked what he had seen and heard, but he still had two questions for us.

Sandage’s Two Questions

By this time, both Scott and I were on pins and needles, wondering what these questions could possibly be and whether we were up to the challenge of answering. Allan’s first question was about the Bible: did we and our pastors believe that the entire Bible was true and trustworthy on every subject it addresses—nature, human nature, God’s nature, historical names, dates, and places? For us, this was a clear “yes.”

His second question was about the universe: what did we believe about the age of the universe? Scott acknowledged that it was billions of years old but that he had no idea how many billions, and then he turned to me. Aware of Allan’s ongoing dispute with Sidney van den Bergh (one of my professors during my graduate training at the University of Toronto), I answered carefully but honestly, “I don’t think it’s as old as your latest publication indicates (16–20 billion years), but I don’t think it’s as young as van den Bergh claims (~10 billion years). Based on my reading and research, I’d say it’s definitely closer to your proposed age than to Sidney’s.“

Allan then asked for my thoughts on the Genesis creation account. I explained that even in my first reading of Genesis, it seemed clear that the creation days must be six consecutive long time periods. After all, the word “day” in Genesis 1:3–2:4 is used for three different time periods: the daylight hours, a single rotation of Earth, and the whole of creation history. I also noted that there was no closure on the seventh creation day. The first six creation days were bracketed by an evening and a morning, indicating to me that each of those days had a start and an end, but there was no evening-morning phrase attached to the seventh day. Those observations, I said, struck me as the answer to the fossil record enigma—for the sudden appearance and abundance of new phyla, classes, and orders of life before the first humans, and few or none afterward. In six major episodes, God prepared for and finally created human life, and on the seventh day, the physical work was done. Now the relational work (God relating to human beings) could begin, but clearly it has not yet ended.

Then Allan turned to Scott for comment. Scott said everything that happened on the sixth day convinced him it must have been more than a 24-hour day. Sandage then wanted to know if other members of the church and church staff believed as we did about creation’s timing and the universe’s age. I could speak only for the pastoral staff, but I assured him there was no dispute.

Allan smiled and sighed with relief. He told us he had become worried that nowhere would he find Christians who upheld belief in biblical inerrancy and also accepted what astronomical observations tell us about the age of the universe. He was glad to have found one, at last, but also disappointed that he had not found others.

Our conversation with Allan that evening went on for at least two hours. We noticed that his wife, Mary, also an astronomer, showed no interest in joining us. In fact, she retreated to another part of the house for the evening. As we were about to leave, Allan told us that when he met Mary, she had a faith in God. Then he added, with deep sadness, “During our first years of marriage, I ruined her faith. I talked her out of believing in God, and now I can’t bring her back.” He asked us to pray that God would somehow bring his wife and two sons to faith in Christ.

Sandage’s Spiritual Development

After our visit, Allan began attending our church and occasionally visited the Sunday class I led (and still lead). However, he did not actively participate. He would listen, politely respond to people’s greetings, and then stay silent during any class discussion or debate.

When Allan heard that I was beginning to write a book on how the physics and astronomy of the universe revealed the existence and attributes of God (The Fingerprint of God), he graciously offered me access to the Carnegie Observatories library, even giving me a key. I spent time there weekly as I researched and wrote, and during those months Allan and I engaged in many brief conversations.

Allan also played a role in the launch of Reasons to Believe. The other pastors and elders at my church were strongly exhorting me to launch a science-faith organization. I was well aware, however, how difficult and likely to fail such a launch would be. Would it not be wiser to join forces with a science-faith organization that already was well established? The only such organization that existed at that time was the Institute for Creation Research (ICR). I felt that if I could persuade the scientists and engineers at the ICR to adopt an old-earth perspective in their apologetics, that there would be no need to launch another organization. I made two trips to the ICR headquarters, first with Norm Geisler and second with Allan Sandage. As I had presumed, the scientists and engineers at the ICR highly respected both Geisler and Sandage and on each visit gave us a whole afternoon to listen to our appeal. However, during the drive home from the second visit, Sandage said it was clear that the ICR would never adopt an old-earth perspective and that I had no choice but to launch Reasons to Believe.

During that second visit to the ICR Sandage and I did not just address science. I learned then and afterwards that Allan knew the Bible better than some pastors. Whenever I brought up a Bible passage in conversation, he immediately recognized the chapter and verse. He loved to discuss biblical doctrine and interpretation with me. Sometimes he joked about this amazing woman named Grace the people at church kept talking about. “She sounds so wonderful. I must meet her,” he would say.

In this humorous way, Allan revealed his painful struggle with grace. He felt deep remorse over past sin in his life and his difficulty in overcoming it. He would comment about feeling unworthy to be called a Christian. He struggled to trust the doctrine of eternal security. It seemed obvious to me that he felt guilt over his relationship with his wife and his inability to restore her faith.

Allan was hesitant to talk about his spiritual struggles with me, and for that I feel deeply disappointed. When one of his sons began attending our church and his daughter-in-law took on a leadership role in our children’s ministry, I thought Allan might be ready to open up, but he was not, at least not with me.

These enduring spiritual struggles may explain what Allan’s long-time astronomy colleague Gustav Tammann wrote in an obituary published in the British journal Nature. According to Tammann, “In the end, he [Sandage] highly valued Christian philosophy but did not find faith.”1 My interactions with Allan persuade me that he did find faith in Jesus Christ as his personal Creator and Savior.

The fact that he expressed conviction over sin, publicly shared the gospel with his non-Christian colleagues, stated his desire to see relatives, friends, and associates embrace the Christian faith, and consistently encouraged and supported my ministry leaves no doubt in my mind. Nevertheless, I can see how his expressions of doubt and frustration over the slow pace of his spiritual growth led some to conclude that he lacked faith.

Sandage, in His Own Words

In closing, I’d like to share some of Allan’s own words on matters of science and faith:

“Those who deny God at the outset by some form of circular reasoning will never find God.”2

“There need be no conflict between science and religion if each appreciates its own boundaries and takes seriously the claims of the other. The proven success of science simply cannot be ignored by the church. But neither can the church’s claim to explain the world at the very deepest level be dismissed. If God did not exist, science would have to (and indeed has) invent the concept to explain what it is discovering at its core.”3

“If there is no God, nothing makes sense.”4

“If there is a God, he must be true both to science and religion. If it seems not so, then one’s hermeneutics (either the pastor’s or the scientist’s) must [be] wrong.”5

“Romans 1:19–21 seems profound. And the deeper any scientist pushes his work, the more profound it does indeed become.”6

“That astronomers have identified the creation event does put astronomical cosmology close to the type of medieval natural theology that attempted to find God by identifying the first cause.”7

“The world is too complicated in all its parts and interconnections to be due to chance alone. I am convinced that the existence of life with all its order in each of its organisms is simply too well put together.”8

“Many scientists are now driven to faith by their very work. In the final analysis it is a faith made stronger through the argument by design.”9

“If you believe anything of the hard science of cosmology, there was an event that happened that can be age dated back in the past. . . . Now that’s an act of creation. Within the realm of science one cannot say any more detail about that creation than the First Book of Genesis.”10

“It was my science that drove me to the conclusion that the world is much more complicated than can be explained by science. It is only through the supernatural that I can understand the mystery of existence.”11

Endnotes

- Gustav A. Tammann, “Allan Sandage (1926–2010): Astronomer Who Measured Expansion Rate of the Universe,” Nature 468, no. 7326 (December 16, 2010): 898, doi:10.1038/468898a.

- Allan Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects on Religious Belief,” in Truth: An International, Inter-Disciplinary Journal of Christian Thought, vol. 1 (1985): 53.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects,” 53.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects,” 53.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects,” 53–54.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects,” 54.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects,” 54.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects, 54.

- Sandage, “A Scientist Reflects, 54.

- Allan Sandage, quoted by Dennis Overbye, Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos: The Story of the Scientific Quest for the Secret of the Universe (New York: Harper-Collins, 1991), 185–186.

- Allan Sandage, quoted by Sharon Begley, “Science Finds God,” Newsweek (July 20, 1998), 44.