Self-Assembly of Protein Machines: Evidence for Evolution or Creation?

I finally upgraded my iPhone a few weeks ago from a 5s to an 8 Plus. I had little choice. The battery on my cell phone would no longer hold a charge.

I’d put off getting a new one for as long as possible. It just didn’t make sense to spend money chasing the latest and greatest technology when current cell phone technology worked perfectly fine for me. Apart from the battery life and a less-than-ideal camera, I was happy with my iPhone 5s. Now I am really glad I made the switch.

Then, the other day I caught myself wistfully eyeing the iPhone X. And, today, I learned that Apple is preparing the release of the iPhone 11 (or XI or XT). Where will Apple’s technology upgrades take us next? I can’t wait to find out.

Have I become a technology junkie?

It is remarkable how quickly cell phone technology advances. It is also remarkable how alluring new technology can be. The next thing you know, Apple will release an iPhone that will assemble itself when it comes out of the box. . . . Probably not.

But, if the work of engineers at MIT ever reaches fruition, it is possible that smartphone manufacturers one day just might rely on a self-assembly process to produce cell phones.

A Self-Assembling Cell Phone

The Self-Assembly Lab at MIT has developed a pilot process to manufacture cell phones by self-assembly.

To do this, they designed their cell phone to consist of six parts that fit together in a lock-in-key manner. By placing the cell phone pieces into a tumbler that turns at the just-right speed, the pieces automatically combine with one another, bit by bit, until the cell phone is assembled.

Few errors occur during the assembly process. Only pieces designed to fit together combine with one another because of the lock-in-key fabrication.

Self-Assembly and the Case for a Creator

It is quite likely that the work of MIT’s Self-Assembly Lab (and other labs like it) will one day revolutionize manufacturing—not just for iPhones, but for other types of products as well.

As alluring as this new technology might be, I am more intrigued by its implications for the creation-evolution controversy. What do self-assembly processes have to do with the creation-evolution debate? More than we might realize.

I believe self-assembly processes strengthen the watchmaker argument for God’s existence (and role in the origin of life). Namely, this cutting-edge technology makes it possible to respond to a common objection leveled against this design argument.

To understand why this engineering breakthrough is so important for the Watchmaker argument, a little background is necessary.

The Watchmaker Argument

Anglican natural theologian William Paley (1743–1805) posited the Watchmaker argument in the eighteenth century. It went on to become one of the best-known arguments for God’s existence. The argument hinges on the comparison Paley made between a watch and a rock. He argued that a rock’s existence can be explained by the outworking of natural processes—not so for a watch.

The characteristics of a watch—specifically the complex interaction of its precision parts for the purpose of telling time—implied the work of an intelligent designer. Employing an analogy, Paley asserted that just as a watch requires a watchmaker, so too, life requires a Creator. Paley noted that biological systems display a wide range of features characterized by the precise interplay of complex parts designed to interact for specific purposes. In other words, biological systems have much more in common with a watch than a rock. This similarity being the case, it logically follows that life must stem from the work of a Divine Watchmaker.

Biochemistry and the Watchmaker Argument

As I discuss in my book The Cell’s Design, advances in biochemistry have reinvigorated the Watchmaker argument. The hallmark features of biochemical systems are precisely the same properties displayed in objects, devices, and systems designed and crafted by humans.

Cells contain protein complexes that are structured to operate as biomolecular motors and machines. Some molecular-level biomachines are strict analogs to machinery produced by human designers. In fact, in many instances, a one-to-one relationship exists between the parts of manufactured machines and the molecular components of biomachines. (A few examples of these biomolecular machines are discussed in the articles listed in the Resources section.)

We know that machines originate in human minds that comprehend and then implement designs. So, when scientists discover example after example of biomolecular machines inside the cell with an eerie and startling similarity to the machines we produce, it makes sense to conclude that these machines and, hence, life, must also have originated in a Mind.

A Skeptic’s Challenge

As you might imagine, skeptics have leveled objections against the Watchmaker argument since its introduction in the 1700s. Today, when skeptics criticize the latest version of the Watchmaker argument (based on biochemical designs), the influence of Scottish skeptic David Hume (1711–1776) can be seen and felt.

In his 1779 work Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Hume presented several criticisms of design arguments. The foremost centered on the nature of analogical reasoning. Hume argued that the conclusions resulting from analogical reasoning are only sound when the things compared are highly similar to each other. The more similar, the stronger the conclusion. The less similar, the weaker the conclusion.

Hume dismissed the original version of the Watchmaker argument by maintaining that organisms and watches are nothing alike. They are too dissimilar for a good analogy. In other words, what is true for a watch is not necessarily true for an organism and, therefore, it doesn’t follow that organisms require a Divine Watchmaker, just because a watch does.

In effect, this is one of the chief reasons why some skeptics today dismiss the biochemical Watchmaker argument. For example, philosopher Massimo Pigliucci has insisted that Paley’s analogy is purely metaphorical and does not reflect a true analogical relationship. He maintains that any similarity between biomolecular machines and human designs reflects merely illustrative analogies that life scientists use to communicate the structure and function of these protein complexes via familiar concepts and language. In other words, it is illegitimate to use the “analogies” between biomolecular machines and manufactured machines to make a case for a Creator.1

A Response Based on Insights from Nanotechnology

I have responded to this objection by pointing out that nanotechnologists have isolated biomolecular machines from the cell and incorporated these protein complexes into nanodevices and nanosystems for the explicit purpose of taking advantage of their machine-like properties. These transplanted biomachines power motion and movements in the devices, which otherwise would be impossible with current technology. In other words, nanotechnologists view these biomolecular systems as actual machines and utilize them as such. Their work demonstrates that biomolecular machines are literal, not metaphorical, machines. (See the Resources section for articles describing this work.)

Is Self-Assembly Evidence of Evolution or Design?

Another criticism—inspired by Hume—is that machines designed by humans don’t self-assemble, but biochemical machines do. Skeptics say this undermines the Watchmaker analogy. I have heard this criticism in the past, but it came up recently in a dialogue I had with a skeptic in a Facebook group.

I wrote that “What we discover when we work out the structure and function of protein complexes are features that are akin to an automobile engine, not an outcropping of rocks.”

A skeptic named Maurice responded: “Your analogy is false. Cars do not spontaneously self-assemble—in that case there is a prohibitive energy barrier. But hexagonal lava rocks can and do—there is no energy barrier to prohibit that from happening.”

Maurice argues that my analogy is a poor one because protein complexes in the cell self-assemble, whereas automobile engines can’t. For Maurice (and other skeptics), this distinction serves to make manufactured machines qualitatively different from biomolecular machines. On the other hand, hexagonal patterns in lava rocks give the appearance of design but are actually formed spontaneously. For skeptics like Maurice, this feature indicates that the design displayed by protein complexes in the cell is apparent, not true, design.

Maurice added: “Given that nature can make hexagonal lava blocks look ‘designed,’ it can certainly make other objects look ‘designed.’ Design is not a scientific term.”

Self-Assembly and the Watchmaker Argument

This is where the MIT engineers’ fascinating work comes into play.

Engineers continue to make significant progress toward developing self-assembly processes for manufacturing purposes. It very well could be that in the future a number of machines and devices will be designed to self-assemble. Based on the researchers’ work, it becomes evident that part of the strategy for designing machines that self-assemble centers on creating components that not only contribute to the machine’s function, but also precisely interact with the other components so that the machine assembles on its own.

The operative word here is designed. For machines to self-assemble they must be designed to self-assemble.

This requirement holds true for biochemical machines, too. The protein subunits that interact to form the biomolecular machines appear to be designed for self-assembly. Protein-protein binding sites on the surface of the subunits mediate this self-assembly process. These binding sites require high-precision interactions to ensure that the binding between subunits takes place with a high degree of accuracy—in the same way that the MIT engineers designed the cell phone pieces to precisely combine through lock-in-key interactions.

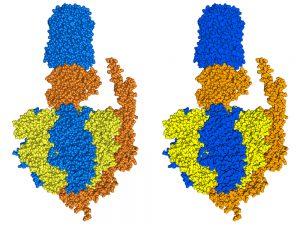

Figure: ATP Synthase is a biomolecular motor that is literally an electrically powered rotary motor. This biomachine is assembled from protein subunits. Credit: Shutterstock

The level of design required to ensure that protein subunits interact precisely to form machine-like protein complexes is only beginning to come into full view.2 Biochemists who work in the area of protein design still don’t fully understand the biophysical mechanisms that dictate the assembly of protein subunits. And, while they can design proteins that will self-assemble, they struggle to replicate the complexity of the self-assembly process that routinely takes place inside the cell.

Thanks to advances in technology, biomolecular machines’ ability to self-assemble should no longer count against the Watchmaker argument. Instead, self-assembly becomes one more feature that strengthens Paley’s point.

The Watchmaker Prediction

Advances in self-assembly also satisfy the Watchmaker prediction, further strengthening the case for a Creator. In conjunction with my presentation of the revitalized Watchmaker argument in The Cell’s Design, I proposed the Watchmaker prediction. I contend that many of the cell’s molecular systems currently go unrecognized as analogs to human designs because the corresponding technology has yet to be developed.

The possibility that advances in human technology will ultimately mirror the molecular technology that already exists as an integral part of biochemical systems leads to the Watchmaker prediction. As human designers develop new technologies, examples of these technologies, though previously unrecognized, will become evident in the operation of the cell’s molecular systems. In other words, if the Watchmaker argument truly serves as evidence for a Creator’s existence, then it is reasonable to expect that life’s biochemical machinery anticipates human technological advances.

In effect, the developments in self-assembly technology and its prospective use in future manufacturing operations fulfill the Watchmaker prediction. Along these lines, it’s even more provocative to think that cellular self-assembly processes are providing insight to engineers who are working to develop similar technology.

Maybe I am a technology junkie, after all. I find it remarkable that as we develop new technologies we discover that they already exist in the cell, and because they do the Watchmaker argument becomes more and more compelling.

Can you hear me now?

Resources

- The Cell’s Design: How Chemistry Reveals the Creator’s Artistry by Fazale Rana (Book)

The Biochemical Watchmaker Argument

- “A Biochemical Watch Found in a Cellular Heath” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “The Provocative Case for Intelligent Design: New Discovery Highlights Machine-Like Character of the Bacterial Flagellum” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Bacterial Flagellum Structure Stacks the Case for Intelligent Design” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Protein Structures Reveal Even More Evidence for Design” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “New Discovery Pumps Up Evidence for Design” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Electron Transport Chain Protein Complexes Rev Up the Case for Design” by Fazale Rana (article)

Challenges to the Biochemical Watchmaker Argument

- “Addressing the Concerns of a Critic and the Case for Intelligent Design” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Nanodevices Make Megascopic Statement” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “A Cornucopia of Evidence for Intelligent Design: DNA Packaging of the T4 Virus” by Fazale Rana (article)

Endnotes

- Massimo Pigliucci and Maarten Boudry, “Why Machine-Information Metaphors are Bad for Science and Science Education,” Science and Education 20, no. 5–6 (May 2011): 453–71; doi:10.1007/s11191-010-9267-6.

- For example, see Christoffer H. Norn and Ingemar André, “Computational Design of Protein Self-Assembly,” Current Opinion in Structural Biology 39 (August 2016): 39–45, doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2016.04.002.