A Response to “Unknown: Cave of Bones”

What makes us human? Are we unique? Are we exceptional? Is it reasonable to think that human beings were made in God’s image, as the Bible teaches?

These questions (and more) are the focus of the third installment of the Netflix documentary series Unknown. This episode, “Cave of Bones,” is directed by Mark Mannucci and tells the stories of paleoanthropologist Lee Berger and his team of collaborators (paleoanthropologist John Hawks, evolutionary anthropologist Agustin Fuentes, and cultural anthropologist Keneiloe Molopayane) who led the excavations of the Rising Star cave system between 2017 and 2022. This cave system houses the remains of the highly enigmatic hominin species, Homo naledi.

| About Homo naledi Discovered in 2013, analysis of the fossil remains of H. naledi revealed a hominin with unique anatomical features that blended Homo and australopithecine characteristics. This creature was about 4 feet in height, weighed about 90 pounds, and had a brain size that approximated a chimpanzee’s. Its lower limbs resembled those of an early member of Homo, indicating that this creature had a humanlike gait. Its arms and torso were reminiscent of an australopithecine, suggesting that this hominin was also adept at climbing and moving through the trees using arboreal locomotion. Its hand structure indicates that H. naledi had the dexterity to manufacture and handle tools. |

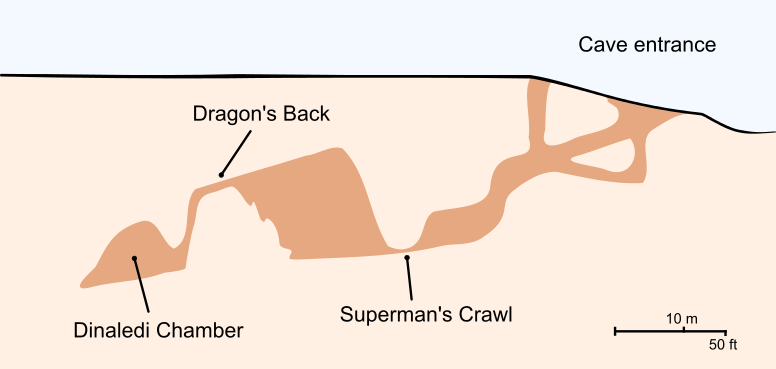

The film masterfully tells the story of the collaborators’ discovery of evidence from the cave system’s Dinaledi Chamber and Dragon’s Back Chamber that—if true—upends everything we think we know about our identity as human beings—regardless of the worldview we hold.

The cinematography in “Cave of Bones” is worth the subscription to Netflix. The video footage of the Rising Star cave system is stunning. So, too, is the videography of the dangerous ascent up Dragon’s Back and the even more risky descent through the chute to the Dinaledi Chamber.

Mannucci expertly captures the allure and intrigue of paleoanthropology. After watching “Cave of Bones,” it’s easy to understand why paleoanthropologists devote their lives to excavating cave sites and studying ancient bones and artifacts. Over and over, Mannucci captures the amazement and unbridled joy that Berger and his team experienced each time they gained new insight into the biology and behavior of H. naledi—insights that they quickly realized have the potential to revolutionize the way we think about ourselves as human beings. Mannucci also does an excellent job of conveying the strange bedfellows made by adventure and tedious hard work that researchers experience when excavating sites for fossil and archaeological treasures.

I particularly enjoyed getting a firsthand look at the cutting-edge scientific tools that are used to excavate cave sites and analyze the finds. My favorite part of the documentary was the scene in which the team encased a rock slab harboring a juvenile specimen of H. naledi with plaster. This unusual step was necessary because the fossils were too fragile to excavate. It was remarkable to see the team’s Herculean effort to transport the plaster slab out of the Dinaledi Chamber through the narrow chute and down Dragon’s Back. It was also fun to watch the way the team used CT technology to image the interior of the rock slab, with Berger eventually traveling to France to use high-energy synchrotron X-rays to get a detailed look at a tool-shaped rock contained in the slab with the juvenile’s remains.

Bombshell Revelations

What fun is a documentary if there aren’t a few bombs to drop? Mannucci drops three high-power “explosives” about H. naledi—and ultimately about us as modern humans. These three revelations add up to one singular idea: human beings are not special after all.

Funerary Practices

Mannuci takes us on the adventure as Berger and his collaborators discover evidence in the Dinaledi Chamber of presumed grave sites where H. naledi ritualistically buried their dead. This hominin species wasn’t simply dropping dead bodies down the chute leading to the Dinaledi Chamber, thereby caching their dead. According to Berger and his team, these hominins were engaging in funerary practices in which they would transport the remains of dead community members through Superman’s Crawl and up Dragon’s Back. Then they carefully lowered the bodies into the Dinaledi Chamber where they were deliberately placed in a grave, along with grave goods (items buried along with the body). If so, then the Dinaledi Chamber was a H. naledi graveyard.

Figure 1: A cartoon of the section of the Rising Star cave system that leads to the Dinaledi Chamber

Credit: Wikipedia

Mannucci interviews Agustin Fuentes about the significance of this claim. According to Fuentes, anthropologists have long regarded funerary practices as something that defined us as modern humans. Some animals deliberately bury their dead. And many animals experience loss and grief when a member of their group dies. But none engage in organized communal ritualistic activities that are packed with meaning as modern humans do.

Funerary practices reflect an awareness and understanding of our own mortality—something that animals apparently lack. These rituals also connote a sense of the afterlife—a recognition that the person who died will continue to exist in another realm. In many cultures, funerary practices are considered an essential step in the transition from our plane of existence to another. Grave goods are often included with the interred body because the community believes their deceased loved one will need these items in the afterlife. Funerary practices also reflect a deep level of care and respect for the deceased members of the community, in which the community sees it as their obligation to come together and invest resources to assist and prepare those who have died for the transition to the afterlife.

Such practices are a manifestation of the combination of four qualities that some anthropologists think make humans unique and exceptional. These include:

- Capacity for symbolism

- Open-ended ability to combine and recombine symbols

- Our theory of mind

- Ability to form complex, hierarchical social structure

As a Christian, I see these properties as scientific descriptors of the image of God. Yet, if H. naledi engaged in funerary practices, then they would be image bearers just like us.

Use of Fire

The second bombshell revealed in the documentary was the evidence Berger and his collaborators discovered for fire use by H. naledi. Presumably, this hominin was making and using fires to light its way through the dark and inaccessible cave passages leading to the Dinaledi Chamber.

Cave Art

The final and most explosive bombshell came near the end of the documentary, when, for the first time, Berger entered the Dinaledi Chamber. Because the chute that drops into the Dinaledi Chamber is quite narrow, only people of small size can be lowered into the Hill Antechamber that opens into the Dinaledi Chamber. For nearly a decade, Berger could only experience the chamber through the video feed provided by anthropologists who were small enough to fit through the chute. In preparation for the 2022 excavations, Berger lost weight and got in shape so he could experience the Dinaledi Chamber firsthand. It is an emotionally gripping scene to see Berger’s response to finally experiencing the cave site that has consumed his life for the past 10 years—a location he never thought he would ever be able to visit.

As Berger begins to look around the cave, he spots something startling: a collection of hatch marks on the pillar that separates the Hill Antechamber from the Dinaledi Chamber. It looks like these hatch marks were deliberately carved into the pillar by a tool much like the one discovered with the H. naledi juvenile that was encased in rock. Berger and his team interpret these markings as evidence that H. naledi made art and had the capacity for symbolism.

These three claims are shocking to many evolutionary scientists who have no commitment to human exceptionalism because H. naledi had a brain size comparable to a chimpanzee. Most paleoanthropologists have long held the view that a large brain size was necessary for advanced cognition. But if these claims stand, they will upend the prevailing thinking among evolutionary biologists about what makes us human and prompt questions about why our brain evolved to be so large. Paleoanthropologist Christopher Stringer (who wasn’t affiliated with the research) said, “These are challenging finds, and they certainly make us think about what it is to be human.”1

Defusing the Bomb

One weakness in “Cave of Bones” is Mannucci’s telling of the H. naledi story as a point-of-view documentary. This style makes Berger’s interpretations of H. naledi’s cognitive capacity and culture quite persuasive. Yet, Mannucci’s approach does a disservice to the viewer because he fails to convey the scientific controversy surrounding Berger and his views of H. naledi. (I detail some of this controversy in a recent article Does H. naledi Undermine the Case for Human Exceptionalism?)

Just before the release of “Cave of Bones,” Berger and his collaborators posted three online scientific papers, as preprints, detailing the discoveries featured in the Netflix documentary.2 These papers were submitted concurrently with the open-access journal eLife for peer review.

This method is called an open-access approach. The traditional approach for publishing scientific papers involves submitting the article(s) to a journal for peer review by experts in the field. Based on the quality of the science, the reviewers decide the paper should be accepted or rejected for publication or should be revised and resubmitted—all of which occurs before the final manuscript is published and available for wide-scale public consumption.

In recent years, there’s been a movement toward an open-access approach to science, in which work is made available before the peer-review process takes place. Sites such as BioRxiv post manuscripts as preprints before or concurrently with the formal peer review process. This path makes scientific findings immediately available. (The formal peer review process can take over a year in some cases.) It also makes the peer review process more transparent.

eLife has adopted an open-access route to publishing scientific works. In their model, a paper is neither accepted nor rejected. It is posted along with the peer reviewers’ comments. The paper can stand as is or the authors can revise it and repost the revised version.

There is much to laud about the open-access strategy to communicating the results of scientific studies. But a word of caution is justified. This approach gives preprints, and even articles posted with peer-reviewed comments, an air of respectability and credibility they may not deserve.

Berger and his collaborators have taken advantage of the open-access model to give the impression that the “Cave of Bones” documentary is undergirded with published scientific support for their claims. But it isn’t.

Paleoanthropologist Andy Herries has chided Berger for this approach, stating “I do have the expectation that there is robust scientific evidence to support such statements before scientists go on massive media campaigns regarding these ideas.”3

It doesn’t appear that the claims about H. naledi cognition and culture are supported by robust scientific evidence. The peer reviews are now coming for the three preprints submitted to eLife and it doesn’t look good for Berger and his coauthors. Respected science journalist Robin McKie, in a piece for The Guardian, quotes three of the peer reviewers who concluded that the papers:

- “Do not present convincing science”

- “Are inadequate, incomplete, and largely assumption-based—rather than evidence based”

- Are “imprudent and incomplete”

Paleoanthropologist Maria Martian-Torres, who wasn’t an official reviewer but coauthored a piece that criticized the Berger team’s claims in the three preprints, told Ewen Callaway for the journal Nature that “I don’t see an anatomical connection. I don’t see a hole or a pit that has been intentionally dug. These hypotheses have been sold with a very strong media campaign before the evidence was ready to support it.”4

Unfortunately, the perception of many paleoanthropologists is that Berger and his collaborators are unresponsive to the concerns raised by the papers’ reviewers. Archaeologist Sven Ouzman, who reviewed the paper describing and interpreting the rock engravings, has expressed concern that the papers are “essentially up there and published, and they can say, ‘we have reviewed the reviewer’s comments, and we thank them for it. But we stand by our arguments.’” 5

So even though Unknown’s “Cave of Bones” episode wows Netflix viewers with a compelling scientific story about H. naledi, one can’t help but wonder if it is little more than a subversive attempt to bypass the scientific process of peer review and supplant it with sensationalized speculation that gains an air of credibility thanks to eLife’s publication model.

Nonscientific Motivations?

All scientists want their work to be placed in the best light. They desire for people to appreciate the significance of their work. Berger and his collaborators are no exception. And they shouldn’t be criticized for these motives. But it appears as if they let their desires get the best of them.

Sadly, paleoanthropology is unusually susceptible to nonscientific influences when advancing ideas. Many fossil and archaeological sites have scant, precious remains available for scientists to study. At best, the remains tell an incomplete story. As a result, paleoanthropologists are left looking through the glass dimly. Yet they are tasked with offering an interpretation of their finds. This is where philosophical and scientific preconceptions and commitments—and career aspirations—can come into play.

Science journalist Jon Mooallem made this point a few years ago in a New York Times piece. He stated:

All sciences operate by trying to fit new data into existing theories. And this particular science, for which the “data” has always consisted of scant and somewhat inscrutable bits of rock and fossil, often has to lean on those meta-narratives even more heavily. . . . Ultimately, a bottomless relativism can creep in: tenuous interpretations held up by webs of other interpretations, each strung from still more interpretations. Almost every archaeologist I interviewed complained that the field has become “overinterpreted”—that the ratio of physical evidence to speculation about that evidence is out of whack. Good stories can generate their own momentum.6

With the expert help of Mannucci, Berger and his collaborators have told a good story about H. naledi. Yet, it’s a tale that signifies nothing. It’s an account that lacks evidential support.

At the end of the day, what we genuinely know about H. naledi doesn’t challenge the notion of human exceptionalism. And for Christians, it doesn’t undermine the biblical claim that we are uniquely made in God’s image—the crown of creation.

We do, indeed, stand alone. Humans are the only creatures who have ever lived that have the capacity to create the enterprise we call science—giving us tools to systematically investigate and understand the world. We are the only creatures who have the wherewithal to ask metaphysical questions about who we are and our place in the cosmos. And we are the only creatures who have the capacity to tell stories designed to answer these questions.

Resources

- Who Was Adam? A Creation Model Approach to the Origin of Humanity by Fazale Rana (book)

- “Does Homo naledi Undermine the Case for Human Exceptionalism?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- Stars, Cells, and God: Homo naledi Art? and Sandgrouse Features by Fazale Rana and Jeff Zweerink (video)

- “Were Neanderthals People, Too? A Response to Jon Mooallem” by Fazale Rana (article)

Endnotes

- Alison George, “Homo naledi May Have Made Etchings on Cave Walls and Buried Its Dead,” New Scientist, June 5, 2023.

- Lee R. Berger et al., “241,000 to 335,000 Years Old Rock Engravings Made by Homo naledi in the Rising Star Cave System, South Africa,” BioRxiv (June 5, 2023), doi:10.1101/2023.06.01.543133; Lee R. Berger et al., “Evidence for Deliberate Burial of the Dead by Homo naledi,” BioRxiv (June 5, 2023), doi:10.1101/2023.06.01.543127; Agustin Fuentes et al., “Burials and Engravings in a Small-Brained Hominin, Homo naledi, from the Late Pleistocene: Contexts and Evolutionary Implications,” BioRxiv (June 5, 2023), doi:10.1101/2023.06.01.543135.

- Robin McKie, “Were Small-Brained Humans Intelligent? Row Erupts Over Scientists’ Claims,” The Guardian (July 22, 2023).

- Ewen Callaway, “Sharp Criticism of Controversial Ancient-Human Claims Tests eLife’s Revamped Peer-Review Model,” Nature 620 (July 25, 2023): 13–14, doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02415-w.

- Callaway, “Sharp Criticism.”

- Jon Mooallem, “Neanderthals Were People, Too,” New York Times Magazine, January 11, 2017.