Not-So-Fast Neutrinos

What travels faster than the speed of light? You know the punchline: gossip.

Well, it wasn’t exactly scuttlebutt, but a team of scientists created quite a stir in the physics and astronomy community last September (2011) with a subatomic particle speed measurement. According to their research, neutrinos traveled from the France/Switzerland border to a detector in Italy at superluminal (faster-than-light) speeds. Numerous popular and semitechnical publications as well as countless blogs reported and discussed the finding, and rightfully so. If the result withstands scientific scrutiny it would undermine one key tenet of Albert Einstein’s almost-universally-accepted general relativity.

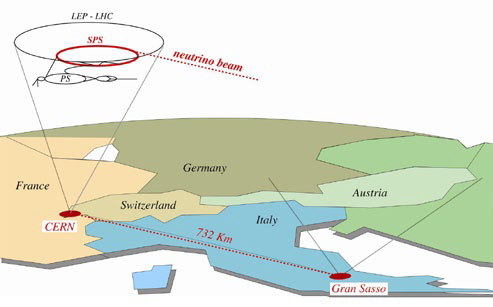

Using the powerful particle accelerators at CERN (Geneva), the research team directed a beam of neutrinos at a detector more than 450 miles away in Gran Sasso, Italy. After accounting for distances, reading clocks, and checking a slew of other details, the OPERA collaboration announced that their measurements showed the neutrinos had made the journey faster than the speed of light.1

Although many additional papers have appeared in the scientific literature, no other experiments have verified the OPERA result. Consequently, most scientists take a skeptical view of superluminal neutrinos.

In fact, other analyses provide a strong counterclaim. For example, ICARUS (another neutrino detector at Gran Sasso utilizing a different timing technique) data shows the propagation time slightly less than the speed of light—as expected since neutrinos have a small mass.2 Also, theoretical work by two prominent physicists demonstrates that superluminal neutrinos would lose energy too rapidly to match the energies detected by the OPERA analysis.3 Other obstacles such as clock synchronization and improperly seated cables also raise doubts that the neutrinos detected by OPERA actually exceeded the speed of light.

With contradictory stories appearing in the popular press, some level of confusion is understandable. Three points can help bring clarity. First, given the enormous impact on rigorously tested science that superluminal neutrinos would cause, the scientific community demonstrated a healthy skepticism, awaiting further data that would either confirm or falsify the OPERA results. Second, the whole process demonstrates the integrity of the scientific process. The OPERA collaboration carefully checked its analysis, published the results for further scrutiny by the larger community, and did not take offense at the general skepticism and subsequent contrary findings. Third, the OPERA, ICARUS, and two other collaborations plan an imminent experimental run that should provide data settling the issue one way or the other.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Faster-than-light neutrinos certainly fall into the category of an extraordinary claim. As it stands now, it does not appear that extraordinary evidence backs up the claim. Consequently, it looks like Einstein’s theory of general relativity––a unifying principle of physics and a tool for understanding features of our universe––still rests on solid footing.

Endnotes

- The OPERA Collaboration, “Measurement of the Neutrino Velocity with the OPERA Detector in the CNGS Beam.”

- Marc Antonello et al., “Measurement of the Neutrino Velocity with the ICARUS Detector at the CNGS Beam.” See figure 3 specifically for a comparison of the OPERA and ICARUS measurements.

- Anthony G. Cohen and Sheldon L. Glashow, “New Constraints on Neutrino Velocities.”