From Dust to Planets

When the Bible tell us that we have been made from the “dust of the earth,” and will eventually “return to the dust,” it is more true than perhaps the authors realized.

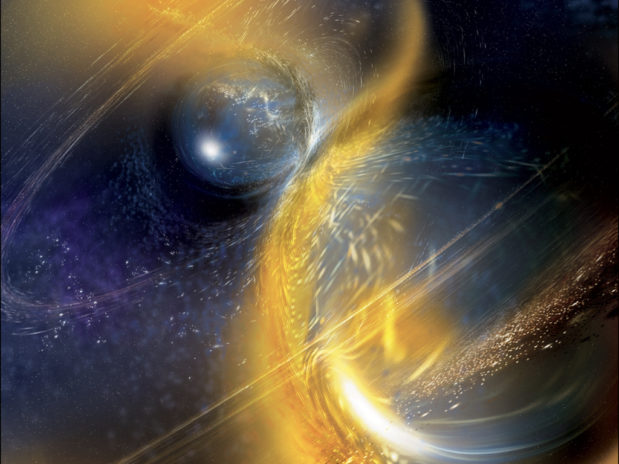

Prevailing theory for the formation of planetsmaintains that they form when dust particles in the disk of material rotating around a central star begin to stick together in clumps (just like the dust under my bed!). Gradually they grow in size, from particles the size of sand, to pebbles, rocks, and eventually boulders as big as a meter across. Next, these boulder-sized objects aggregate into objects called planetesimals that can be many kilometers across. Finally, gravity takes over and draws these planetesimals together to form planets.

Scientists have accounted for most of the physical processes necessary to bring about the accumulation of material to finally form planets, except for that one step of going from boulders to planetesimals. On occasion it has been called one of the major unsolved problems in planet formation, and has often been the focus of dispute by some in the young-earth creationist community as grounds for rejecting this explanation for how solar systems like our own were formed.

New research could help resolve the issue. In a paper published in the August 30, 2007 issue of Nature, Anders Johansen and several of his colleagues describe a set of simulations that, to their knowledge, for the first time permits accurate and complete modeling of how these objects go from meter-sized boulders to kilometer-scale planetesimals.

The team needed to solve two major problems: (1) boulders are not expected to stick together very easily because of the weakness of their gravitational interaction, and (2) the time to interact is short because the objects tend to spiral into the central star in only a few tens of orbits, due to the “headwind” from slower rotating gas.

The results of their simulations demonstrate, however, that boulders can, indeed, collapse together under the force of gravity. What they show is that some regions in the disk randomly undergo local increases in the density of boulders. Then gravity can act over a long-enough period of time and with sufficient strength to build up larger bodies.

While the authors are cautious about claiming to have resolved all the difficulties, they do offer a possible path for filling this gap in planet formation. Once again, more detailed studies have yielded an explanation for a particular phenomenon that at first had been criticized.

Certainly there are areas of science where the lack of an explanation is grounds for abandoning a theory, but this is not one of them. Instead, to (the planetary) dust we shall return.