Differences in Human and Neanderthal Brains Explain Human Exceptionalism

When I was a little kid, my mom went through an Agatha Christie phase. She was a huge fan of the murder mystery writer and she read all of Christie’s books.

Agatha Christie was caught up in a real-life mystery of her own when she disappeared for 10 days in December 1926 under highly suspicious circumstances. Her car was found near her home, close to the edge of a cliff. But, she was nowhere to be found. It looked as if she disappeared without a trace, without any explanation. Eleven days after her disappearance, she turned up in a hotel room registered under an alias.

Christie never offered an explanation for her disappearance. To this day, it remains an enduring mystery. Some think it was a callous publicity stunt. Some say she suffered a nervous breakdown. Others think she suffered from amnesia. Some people suggest more sinister reasons. Perhaps, she was suicidal. Or maybe she was trying to frame her husband and his mistress for her murder.

Perhaps we will never know.

Like Christie’s fictional detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, paleoanthropologists are every bit as eager to solve a mysterious disappearance of their own. They want to know why Neanderthals vanished from the face of the earth. And what role did human beings (Homo sapiens) play in the Neanderthal disappearance, if any? Did we kill off these creatures? Did we outcompete them or did Neanderthals just die off on their own?

Anthropologists have proposed various scenarios to account for the Neanderthals’ disappearance. Some paleoanthropologists think that differences in the cognitive capabilities of modern humans and Neanderthals help explain the creatures’ extinction. According to this model, superior reasoning abilities allowed humans to thrive while Neanderthals faced inevitable extinction. As a consequence, we replaced Neanderthals in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia when we first migrated to these parts of the world.

Computational Neuroanatomy

Innovative work by researchers from Japan offers support for this scenario.1 Using a technique called computational neuroanatomy, researchers reconstructed the brain shape of Neanderthals and modern humans from the fossil record. In their study, the researchers used four Neanderthal specimens:

- Amud 1 (50,000 to 70,000 years in age)

- La Chapelle-aux Saints 1 (47,000 to 56,000 years in age)

- La Ferrassie 1 (43,000 to 45,000 years in age)

- Forbes’ Quarry 1 (no age dates)

They also worked with four Homo sapiens specimens:

- Qafzeh 9 (90,000 to 120,000 years in age)

- Skhūl 5 (100,000 to 135,000 years in age

- Mladeč 1 (35,000 years in age)

- Cro-Magnon 1 (32,000 years in age)

Researchers used computed tomography scans to construct virtual endocasts (cranial cavity casts) of the fossil brains. After generating endocasts, the team determined the 3D brain structure of the fossil specimens by deforming the 3D structure of the average human brain so that it fit into the fossil crania and conformed to the endocasts.

This technique appears to be valid, based on control studies carried out on chimpanzee and bonobo brains. Using computational neuroanatomy, researchers can deform a chimpanzee brain to accurately yield the bonobo brain, and vice versa.

Brain Differences, Cognitive Differences

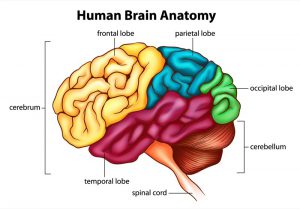

The Japanese team learned that the chief difference between human and Neanderthal brains is the size and shape of the cerebellum. The cerebellar hemisphere is projected more toward the interior in the human brain than in the Neanderthal brain and the volume of the human cerebellum is larger. Researchers also noticed that the right side of the Neanderthal cerebellum is significantly smaller than the left side—a phenomenon called volumetric laterality. This discrepancy doesn’t exist in the human brain. Finally, the Japanese researchers observed that the parietal regions in the human brain were larger than those regions in Neanderthals’ brains.

Because of these brain differences, the researchers argue that humans were socially and cognitively more sophisticated than Neanderthals. Neuroscientists have discovered that the cerebellum helps motor functions and higher cognition by contributing to language function, working memory, thought, and social abilities. Hence, the researchers argue that the reduced size of the right cerebellar hemisphere in Neanderthals limits the connection to the prefrontal regions—a connection critical for language processing. Neuroscientists have also discovered that the parietal lobe plays a role in visuo-spatial imagery, episodic memory, self-related mental representations, coordination between self and external spaces, and sense of agency.

On the basis of this study, it seems that humans either outcompeted Neanderthals for limited resources—driving them to extinction—or simply were better suited to survive than Neanderthals because of superior mental capabilities. Or perhaps their demise occurred for more sinister reasons. Maybe we used our sophisticated reasoning skills to kill off these creatures.

Did Neanderthals Make Art, Music, Jewelry, etc.?

Recently, a flurry of reports has appeared in the scientific literature claiming that Neanderthals possessed the capacity for language and the ability to make art, music, and jewelry. Other studies claim that Neanderthals ritualistically buried their dead, mastered fire, and used plants medicinally. All of these claims rest on highly speculative interpretations of the archaeological record. In fact, other studies present evidence that refutes every one of these claims (see Resources).

Comparisons of human and Neanderthal brain morphology and size become increasingly important in the midst of this controversy. This recent study—along with previous work (go here and here)—indicates that Neanderthals did not have the brain architecture and, hence, cognitive capacity to communicate symbolically through language, art, music, and body ornamentation. Nor did they have the brain capacity to engage in complex social interactions. In short, Neanderthal brain anatomy does not support any interpretation of the archaeological record that attributes advanced cognitive abilities to these creatures.

While this study provides important clues about the disappearance of Neanderthals, we still don’t know why they went extinct. Nor do we know any of the mysterious details surrounding their demise as a species.

Perhaps we will never know.

But we do know that in terms of our cognitive and social capacities, human beings stand apart from Neanderthals and all other creatures. Human brain biology and behavior render us exceptional, one-of-a-kind, in ways consistent with the image of God.

Resources

- Who Was Adam? A Creation Model Approach to the Origin of Humanity by Fazale Rana with Hugh Ross (book)

- “Were Neanderthals People, Too? A Response to Jon Mooallem” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “One-of-a-Kind: Three Discoveries Affirm Human Uniqueness” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Paleoanthropologists Mixed-Up about Neanderthal Behavior” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Rabbit Burrowing Churns Claims about Neanderthal Burials” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “New Research Douses Claim that Neanderthals Mastered Fire” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Make Glue?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Self-Medicate?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Make Jewelry?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Are Perforated Shells Evidence for Neanderthal Symbolism?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Do Neanderthal Cave Structures Challenge Human Exceptionalism?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Bury Their Dead with Flowers?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Neanderthal Burials ‘Deep Sixed’” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Make Art?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Did Neanderthals Have the Brains to Make Art?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Neanderthal Brains Make Them Unlikely Social Networkers” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Darwin’s Problem: The Origin of Language” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Speaking about a Controversy, Part 1 of 2” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Speaking about a Controversy, Part 2 of 2” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Science News Flash: Chimps Use Tools to Fish for Algae” by Fazale Rana (article)

Endnotes

- Takanori Kochiyama et al., “Reconstructing the Neanderthal Brain Using Computational Anatomy,” Science Reports 8 (April 26, 2018): 6296, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24331-0.