Discovery Challenges Cause of Earth’s Climate Stability

Climate change discussions can range from casual to serious, from dismissive to alarmist. But how many people talk about Earth’s current period of extreme climate stability and how we got it? Scientists have been debating the cause of our 9,500-year stable climate, and their findings stand to provide further understanding into an event that has made high-tech human civilization possible.

Characteristics of the Ice Age Cycle

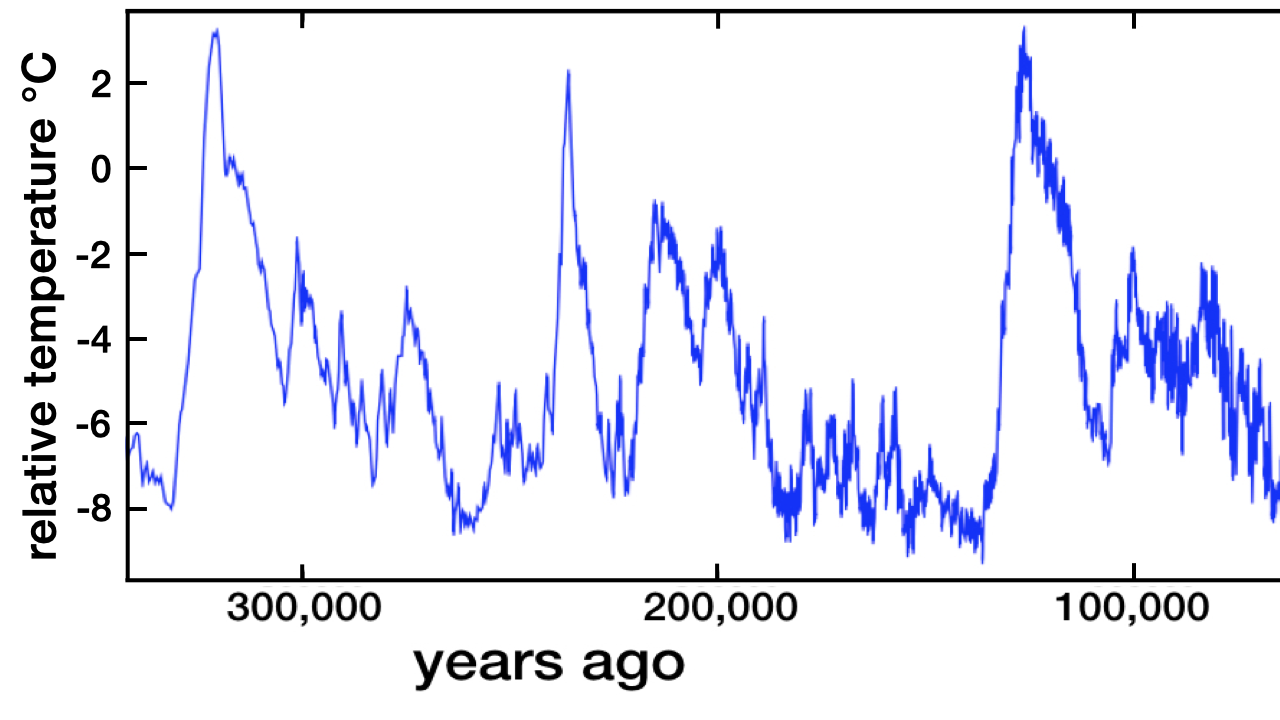

For the past 2.58 million years, Earth’s ice age cycle has been characterized by long periods of 20–23% surface ice coverage (ice ages) interspersed by brief episodes (interglacials) where only about 10% of Earth’s surface is ice-covered. In the transition from an ice age to an interglacial, the global mean (average) temperature rises quickly and steadily by about 10–12°C to a maximum of 2–3°C above the current temperature. Then, almost as quickly (but not so steadily), it falls by about 10°C, dropping the world back into an ice age. Figure 1 shows this pattern for the three ice ages that preceded the most recent one.

Figure 1: Global Mean Temperature Record for the Past Three Ice Ages. The 0°C point equals the present global mean temperature.

Data curve credit: Robert A. Rohde, Global Warming Art Project, CC-by-SA; diagram credit: Hugh Ross

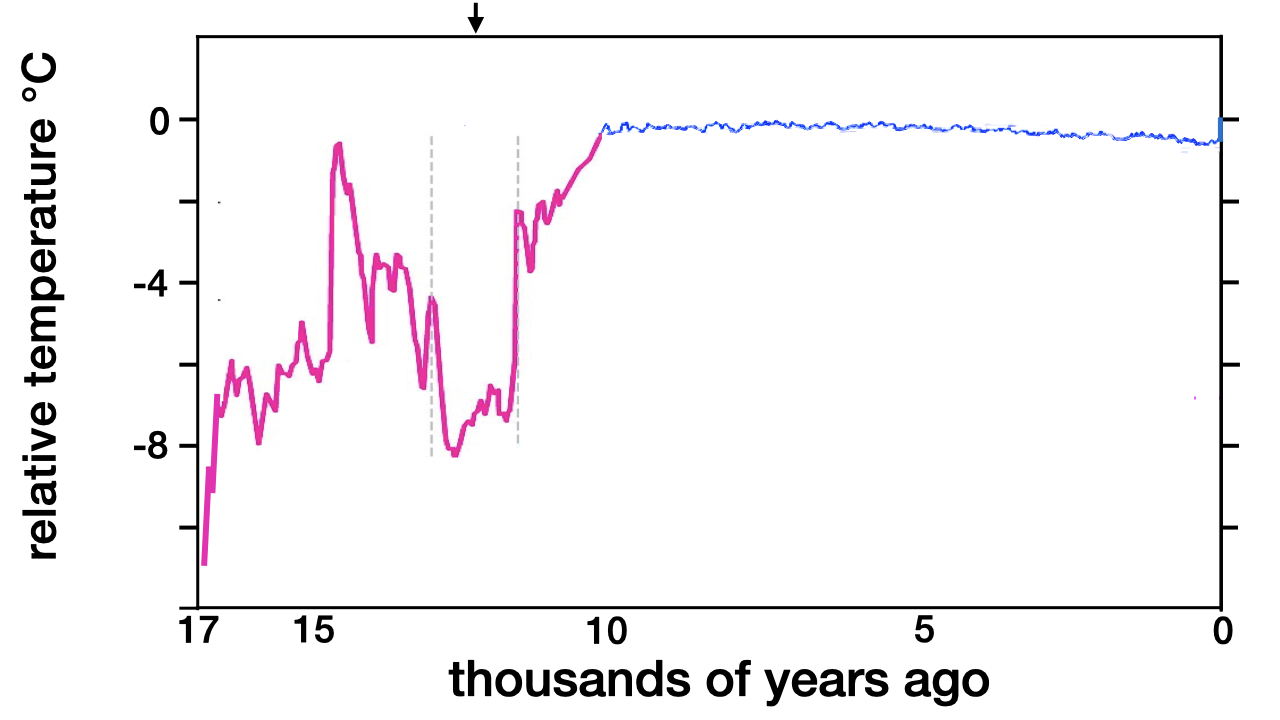

However, the circumstances were different coming out of the last ice age. Instead of the global mean temperature rising sharply and steadily toward a maximum of about 2–3°C above the present, the rise was interrupted approximately 12,900 years ago by about a 1,200-year-long major global cooling event, the Younger Dryas (YD). Figure 2 shows how the YD prevented the global mean temperature from rising to its typical interglacial maximum and made possible the past 9,500 years of extreme climate stability.

Figure 2: Global Mean Temperature Record for the Past 17,000 Years. The dotted lines and the arrow show the Younger Dryas cooling event.

Data credit: United States Geological Survey; diagram credit: Hugh Ross

Impact Event Challenged

The cause of the YD has been a subject of scientific debate for several decades. In my latest book, Weathering Climate Change, I presented the evidence for the recently discovered Hiawatha impactor as the causal agent for the YD.1 This evidence refers to a large crater depression (about 19 miles wide) beneath Greenland’s ice sheet in the Hiawatha Glacier region. The crater is thought to have been caused by an asteroid striking around 12,800 years ago that triggered Earth’s current period of climate stability.

Now, a team of 23 scientists from China, Spain, Austria, and the USA has published dating measurements that they claim rule out the northwest Greenland Hiawatha impactor as the cause of the YD.2 Instead, they suggest a worldwide oceanic reorganization occurred in response to an “abrupt North Atlantic climate change.”3

The team used the uranium-thorium dating technique to improve an analysis of speleothem oxygen-isotope data in order to produce the most accurate date for the onset of the YD. Their date for the onset of the YD in the North Atlantic is 12,870±30 years ago. They cite two independent carbon-14 dating determinations for the Hiawatha impact event: one yielding a date of 12,835–12,735 years ago, the other a date of 12,875–12,775 years ago. While the latter date overlaps their measurement for the YD onset, they argue that there would be about a 50-year lag between the impact event and the cooling of the North Atlantic Ocean. Hence, they conclude that the Hiawatha impactor could not be the cause of the YD. They support their conclusion by pointing out that it would be inconceivable for the Hiawatha impactor to trigger the YD and not leave an unmistakable imprint in the Greenland ice core records.4

Analyzing the Challenge

In reading through the team’s paper I was not persuaded that they had successfully eliminated the Hiawatha impactor as the cause of the YD. Here are five reasons why.

- Systematic errors were not considered. I agree that the statistical error on their date for the YD onset is only ±30 years, but I do not agree that the possible systematic errors can be ignored. In a previous Today’s New Reason to Believe article I explained that the uranium-thorium dating method measures how long a sample has first been precipitated from water based on the fact that thorium is not soluble in water while uranium is.5 Determining the ratio of thorium-230 to uranium-234 in a sample yields the time since its precipitation if, and only if: (a) one knows that the sample is entirely from a single rapid precipitation event, and (b) the sample subsequently has not suffered any significant disturbances or contamination. If (a) and (b) are not precisely known, as is the case with the team’s analysis of speleothem oxygen-isotope data, along with their ±30 years probable statistical error there will be an additional, and possibly sizable, probable systematic error. Therefore, the dates for the Hiawatha impact and the onset of the YD may not be discordant.

- Glacial melt into the North Atlantic was probably deposited rapidly. I do not think it would take as long as 50 years for the Hiawatha impactor to bring on the onset of the YD. In Weathering Climate Change I presented the geological and oceanographic evidence that the drainage of Lake Agassiz, an enormous glacial lake larger than Hudson Bay, was suddenly altered from flowing into the Gulf of Mexico to flowing into the Beaufort Sea (Arctic Ocean) and the Gulf of St. Lawrence (eastern Canada) about 12,900 years ago.6 It would take the raining down of ice, water, rocks, and debris from a major impact event to explain such a sudden and dramatic drainage alteration. Given the proximity of Lake Agassiz to the Hiawatha impactor site in northwest Greenland, it would have received an especially intense bombardment. The drainage alteration would have sent a massive rush of glacial meltwater into the North Atlantic Ocean in significantly less than 50 years. This meltwater would have been accompanied by at least 1,500 billion tons of melted Greenland ice that would have entered the North Atlantic almost immediately.

- The Hiawatha impactor was not a minor asteroid. The impact left behind a crater 31.1 kilometers (19.3 miles) in diameter and 930 meters (3,050 feet) in depth below the Greenland Hiawatha ice field. The crater rim is 320 meters (1,050 feet) high. These dimensions and chemical analysis of fragments from the impactor establish that the impactor was a Duchesne iron asteroid 1.5 kilometers (0.93 miles) in diameter. It is inconceivable that such a large iron asteroid striking northwest Greenland would yield a negligible or only minor global cooling effect. The impactor would have generated a global cooling event on the scale of the YD. There is no other comparable cooling event that has occurred during the past 15,000 years.

- The YD is unprecedented in the ice age cycle. Something unprecedented and dramatic had to cool the North Atlantic Ocean to the degree that it did. As noted, the team of 23 scientists acknowledged that the cause of the YD brought about an “abrupt North Atlantic climate change.” A sudden infusion of a massive amount of glacial meltwater into the North Atlantic Ocean would explain such an abrupt and dramatic climate change. A mere alteration of North Atlantic Ocean currents by causes localized to the North Atlantic would yield too tepid of a change.

- The lack of imprint can be explained. A published explanation in the astronomical literature illustrates why the Hiawatha impactor would not leave an unmistakable imprint in the Greenland ice core records. Scientists can cite models explaining why impacts on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn do not yield a spread of impact debris in the vicinity of the impact site. These models would apply to the Hiawatha impactor. The impactor struck a location that had over a 3,000-foot thickness of ice, thereby suppressing an imprint in the Greenland ice core records.

Better Understanding of an Extraordinary Event

By these critiques I do not intend to imply that the 23 scientists failed to make important scientific advances. They propelled the way forward to coming up with more accurate and reliable dates for both the YD and the Hiawatha impactor. Their most important contribution was showing that the YD cooling event began in the North Atlantic Ocean and spread along a north to south route all the way to Antarctica. They showed that the cooling in Antarctica lagged the cooling in the North Atlantic by 200±100 years. They also demonstrated that the termination of the YD began in the Southern Ocean region around Antarctica about 11,900 years ago and concluded in the North Atlantic 11,700–11,610 years ago.

The team provided additional evidence that the YD played a crucial role in preventing a global mean temperature rise to 2–3°C above the present and making possible the past 9,500 years of extreme climate stability. Without this unprecedented period of stability in the midst of an ice cycle, it would not be possible for the rise of a human population in the billions or for humanity to enjoy global high-technology civilization. Given how extremely extraordinary the past 9,500 years have been, every human is compelled to ask why we’ve been so fortunate. An additional question to ponder is, What is the purpose of it all?

Featured image: Hiawatha Ice Field in Northwestern Greenland

Image credit: NASA

Endnotes

- Hugh Ross, Weathering Climate Change (Covina, CA: RTB Press, 2020), 150–61.

- Hai Cheng et al., “Timing and Structure of the Younger Dryas Event and Its Underlying Climate Dynamics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 117, no. 38 (September 22, 2020): 23408–17, doi:10.1073/pnas.2007869117.

- Cheng et al., “Timing and Structure,” 23415.

- Cheng et al., “Timing and Structure,” 23414.

- Hugh Ross, “Errors in Human Origins Dates,” Today’s New Reason to Believe (blog), June 29, 2020, /todays-new-reason-to-believe/read/todays-new-reason-to-believe/2020/06/29/errors-in-human-origins-dates.

- Ross, Weathering Climate Change, 152–59.